Home » Wheat

Category Archives: Wheat

One Well-Timed Shot: Rethinking Split Nitrogen Applications in Wheat production

Brian Arnall, Precision Nutrient Management Specialist

Samson Abiola, PNM Ph.D. Student.

Nitrogen is the most yield limiting nutrient in wheat production, but it’s also the most unpredictable. Apply it too early, and you risk losing it to leaching or volatilization before your crop can use it. Apply it too late, and your wheat has already determined its yield potential; you’re just feeding protein at that point. For decades, the conventional wisdom has been to split nitrogen applications: put some down early to get the crop going, then come back later to apply again. But does splitting actually work? And more importantly, when is the optimal window to apply nitrogen if you want to maximize both yield and protein quality? We spent three years across different Oklahoma locations testing every timing scenario to answer these questions.

How We Tested Every Nitrogen Timing Scenario in Oklahoma Wheat

Between 2018 to 2021, we conducted field trials at three Oklahoma locations, including Perkins, Lake Carl Blackwell, and Chickasha, representing different soil types and growing conditions across the state. We tested three nitrogen rates: 0, 90, and 180 lbs N/ac, applied as urea at five critical growth stages based on growing degree days (GDD). These timings were 0 GDD (preplant, before green-up), 30 GDD (early tillering), 60 GDD (active tillering), 90 GDD (late tillering, approximately Feekes 5-6), and 120 GDD (stem elongation, approaching jointing). We also compared single applications at each timing against split applications, where half the nitrogen (45 lbs N ac-1) went down preplant, and the other half was applied in-season (45 lbs N ac-1).

The Sweet Spot: Yield and Protein at the 90 lbs N/ac Rate

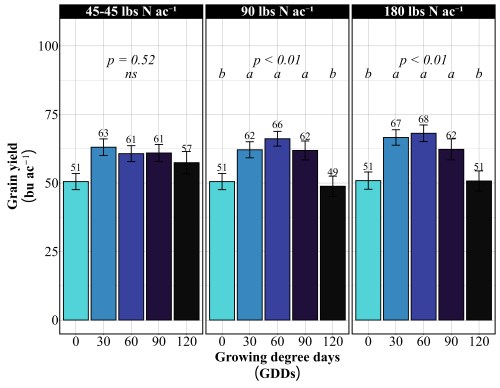

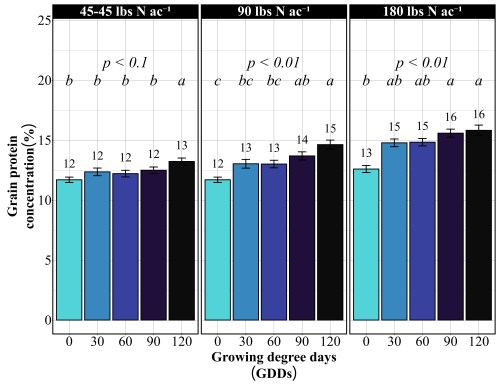

Across all site-years, at the 90 lbs N/ac rate, timing had a significant impact on both yield and protein. The highest yields came from the 30 and 90 GDD timings, producing 62 to 66 bu/ac, with 60 GDD reaching the peak (Figure 1). Protein at these early timings stayed relatively modest at 13%. The 90 GDD timing delivered 62 bu/ac with 14% protein matching the yield of the 30 GDD application but pushing protein a percentage higher (Figure 2). The real problem appeared at 120 GDD. Delaying application until stem elongation dropped yields to just 49 bu/ac, even though protein climbed to 15%. That’s a 13 bushel penalty compared to the 90 GDD timing. At current wheat prices per bushel, that late application may cost farmers over $100 per acre in lost revenue. By 120 GDD, the crop has already determined its yield potential tillers are set, head numbers are locked in and nitrogen applied at this stage can only be directed toward protein synthesis, not building more yield components.

More Nitrogen Does not lead to high yield

Doubling the nitrogen rate to 180 lbs N/ac revealed something critical, more nitrogen doesn’t mean more yield. The yield pattern remained nearly identical to the 90 lbs N/ac rate. The 60 GDD timing produced the highest yield at 68 bu/ac, followed closely by 30 GDD at 67 bu/ac. The 90 GDD timing yielded 62 bu/ac, and the 120 GDD timing again crashed to 51 bu/ac. The only difference between the two rates was protein concentration (Figure 2). At 180 lbs N/ac, protein levels increased across all timings: 13% at preplant, 15% at both 30 and 60 GDD, 15-16% at 90 GDD, and 16% at 120 GDD. This confirms a fundamental principle: once farmers supply enough nitrogen to maximize yield potential, which occurred at 90 lbs N/ac in these trials, additional nitrogen only increases grain protein. It does not build more bushels. Unless farmers are receiving premium payments for high-protein wheat, that extra 90 lbs of nitrogen represents a cost with no yield return.

Should farmers split their nitrogen application?

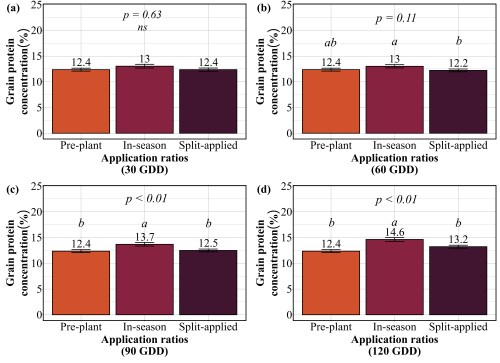

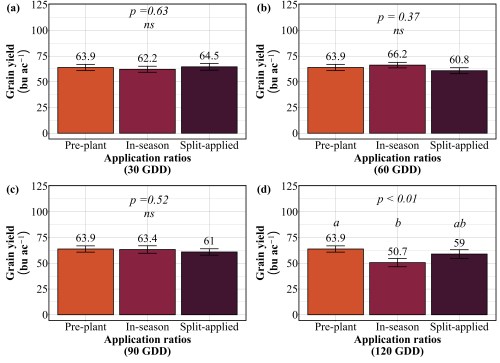

Now that timing has been established as critical, the next question becomes: should farmers split their nitrogen applications, or is a single application sufficient? The conventional recommendation has been to split nitrogen apply part preplant to support early growth and tillering, then return with a second application later in the season to boost protein and finish the crop. But does the data support this practice? We compared three strategies at each timing: applying all nitrogen preplant, applying all nitrogen in-season at the target timing, or splitting nitrogen equally between preplant and in-season timing. The goal was to determine whether the extra trip across the field will deliver better results.

Our findings revealed that splitting provided no consistent advantage. At 30 GDD, all three strategies preplant, in-season, and split performed identically, producing 62-65 bu/ac with 12-13% protein (Figure 3 and 4). No statistical differences existed among them. At 60 GDD, similar pattern was held. Yields ranged from 61 to 66 bu/ac and protein stayed at 12-13% regardless of whether farmers applied all nitrogen preplant, all at 60 GDD, or split between the two. At 90 GDD, the single in-season application actually outperformed the split. While yields remained similar across all three methods (61-64 bu/ac), the in-season application delivered significantly higher protein at 13.7% compared to 12.4% for preplant and 12.5% for split applications. This suggests that concentrating nitrogen at 90 GDD, rather than diluting it across two applications, allows more efficient incorporation into grain protein. The only timing where splits appeared beneficial was 120 GDD, where the split application yielded 59 bu/ac compared to 51 bu/ac for the single late application. But this is not a win for splitting, it simply demonstrates that applying all nitrogen at 120 GDD is too late and putting half down earlier salvages some of the yield loss. Across all timings tested, splitting nitrogen into two applications offered no agronomic advantage over a single well-timed application, meaning farmers are making an extra pass for no gain in yield or protein.

Practical Recommendations for Nitrogen Management

Based on three years of field data, farmers should target the 90 GDD timing (late tillering, Feekes 5-6) for their main nitrogen application to achieve the best balance between yield and protein. This window typically falls in late February to early March in Oklahoma, though farmers should monitor crop development rather than relying solely on the calendar apply when wheat shows multiple tillers, good green color, and vigorous growth. A rate of 90 lbs N/ac maximized yield in these trials; higher rates only increased protein without adding bushels, so farmers should only exceed this rate if receiving premium payments for high-protein wheat. Splitting nitrogen applications provided no advantage at any timing, meaning a single well-timed application at 90 GDD is sufficient for most Oklahoma wheat production systems. The exception would be sandy soils with high leaching potential, where splitting may reduce nitrogen loss. Farmers should avoid delaying applications until 120 GDD or later, as this timing consistently resulted in 15-25 bushel per acre yield losses even though protein increased. For farmers specifically targeting premium protein markets, a two-step strategy works best: apply 90 lbs N/ac at 90 GDD to establish yield potential and baseline protein, then follow with a foliar application of 20-30 lbs N/ac at flowering to push protein above 14% without sacrificing yield. Finally, weather conditions matter hot, dry forecasts increase volatilization risk and reduce uptake efficiency, so farmers should consider moving applications earlier if low humidity conditions are expected.

Split Application Caveat * Note from Arnall.

The caveat to the it only takes one pass, is high yielding >85+ bpa, environments. In these situation I still have not found any value for preplant nitrogen application. I have seen however a split spring application is valuable. Basically putting on 30-50 lbs at green-up, with the rest following at jointing (hollowstem). The method tends to reduce lodging in the high yielding environments.

This work was published in Front Plant Sci. 2025 Nov 6;16:1698494. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1698494

Split nitrogen applications provide no benefit over a single well timed application in rainfed winter wheat

Another reason to N-Rich Strip.

Yet just one more data set showing the value of in-season nitrogen and why the N-Rich Strip concept works so well.

Questions or comments please feel free to reach out.

Brian Arnall b.arnall@okstate.edu

Acknowledgements:

Oklahoma Wheat Commission and Oklahoma Fertilizer Checkoff for Funding.

Double Crop Options After Wheat (KSU Edition)

Stolen from the KSU e-Update June 5th 2025.

Double cropping after wheat harvest can be a high-risk venture for grain crops. The remaining growing season is relatively short. Hot and/or dry conditions in July and August may cause problems with germination, emergence, seed set, or grain fill. Ample soil moisture this year can aid in establishing a successful crop after wheat harvest. Double-cropping forages after wheat works well even in drier regions of the state.

The most common double crop grain options are soybean, sorghum, and sunflower. Other possibilities include summer annual forages and specialized crops such as proso millet or other short-season summer crops, even corn. Cover crops are also an option for planting after wheat (see the companion eUpdate article “Cover crops grown post-wheat for forage”).

Be aware of herbicide carryover potential

One major planting consideration after wheat is the potential for herbicide carryover. Many herbicides applied to wheat are Group 2 herbicides in the sulfonylurea family with the potential to remain in the soil after harvest. If a herbicide such as chlorsulfuron (Glean, Finesse, others) or metsulfuron (Ally) has been used, then the most tolerant double crop will be sulfonylurea-resistant varieties of soybean (STS, SR, Bolt) or other crops. When choosing to use herbicide-resistant varieties, be sure to match the resistance trait with the specific herbicide (not only the herbicide group) that you used. This is especially true when looking at sunflowers as a double crop. There are sunflowers with the Clearfield trait, which allows Beyond herbicide applications, and ExpressSun sunflowers, which allow an application of Express herbicide. While both of these herbicides are Group 2 (ALS-inhibiting herbicides), the Clearfield trait and ExpressSun are not interchangeable, and plant damage can result from other Group 2 herbicides.

Less information is available regarding the herbicide carryover potential of wheat herbicides to cover crops. There is little or no mention of rotational restrictions for specific cover crops on the labels of most herbicides. However, this does not mean there are no restrictions. Generally, there will be a statement that indicates “no other crops” should be planted for a specified amount of time, or that a bioassay must be conducted prior to planting the crop.

Burndown of summer annual weeds present at planting is essential for successful double-cropping. Assuming glyphosate-resistant kochia and pigweeds are present, combinations of glyphosate with products such as saflufenacil (Sharpen) or tiafenacil (Reviton), or alternative treatments such as paraquat may be required. Dicamba or 2,4-D may also be considered if the soybean varieties with appropriate herbicide resistance traits are planted. In addition, residual herbicides for the double crop should be applied at this time.

Management, production costs, and yield outlooks for double crop options are discussed below.

Soybeans

Soybeans are likely the most commonly used crop for double cropping, especially in central and eastern Kansas (Figure 1). With glyphosate-resistant varieties, often the only production cost for planting double crop soybeans was the seed, an application of glyphosate, and the fuel and equipment costs associated with planting, spraying, and harvesting. However, the spread of herbicide-resistant weeds means additional herbicides will be required to achieve acceptable control and minimize the risk of further development of resistant weeds.

Weed control. The weed control cost cannot really be counted against the soybeans, since that cost should occur whether or not a soybean crop is present. In fact, having soybeans on the field may reduce herbicide costs compared to leaving the field fallow. Still, it is recommended to apply a pre-emergence residual herbicide before or at planting time. Later in the summer, a healthy soybean canopy may suppress weeds enough that a late-summer post-emergence application may not be needed.

Variety selection for double cropping is important. Soybeans flower in response to a combination of temperature and day length, so shifting to an earlier-maturing variety when planting late in a double crop situation will result in very short plants with pods that are close to the ground. Planting a variety with the same or perhaps even slightly later maturity rating (compared to soybeans planted at a typical planting date) will allow the plant to develop a larger canopy before flowering. Planting a variety that is too much later in maturity, however, increases the risk that the beans may not mature before frost, especially if long periods of drought slow growth. The goal is to maximize the length of the growing season of the crop, so prompt planting after wheat harvest time is critical. The earlier you can plant, the higher the yield potential of the crop if moisture is not a limiting factor.

Fertilizer considerations. Adding some nitrogen (N) to double-crop soybeans may be beneficial if the previous wheat yield was high and the soil N was depleted. A soil test before wheat harvest for N levels is recommended. Use no more than 30 lbs/acre of N. It would be ideal to knife-in the fertilizer. If that is not possible, banding it on the soil surface would be acceptable. Do not apply N in the furrow with soybean seed as severe stand loss can occur.

Seeding rates and row spacing. Seeding rate can be slightly increased if soybeans are planted too late in order to increase canopy development. Narrow row spacing (15-inch or less) has often resulted in a yield advantage compared to 30-inch rows in late plantings. Soybeans planted in narrow rows will canopy over more quickly than in wide rows, which is important when the length of the growing season is shortened. Narrow rows also offer the benefits of increasing early-season light capture, suppressing weeds, and reducing erosion. On the other hand, the advantage of planting in wide rows is that the bottom pods will usually be slightly higher off the soil surface to aid harvest. The other consideration is planting equipment. Often, no-till planters will handle wheat residue better and place seeds more precisely than drills, although the difference has narrowed in recent years.

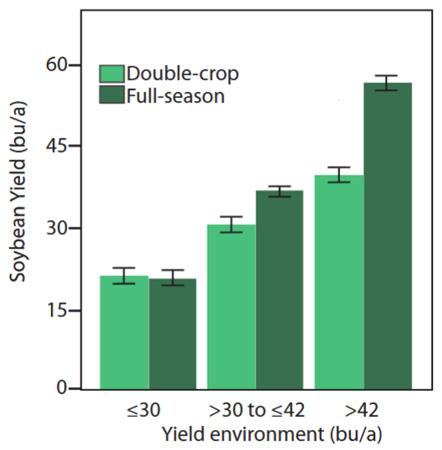

What are typical yield expectations for double-crop soybeans? It varies considerably depending on moisture and temperature, but yields are usually several bushels less than full-season soybeans. A long-term average of 20 bushels per acre is often mentioned when discussing double-crop soybeans in central and northeast Kansas. Rainfall amount and distribution can cause a wide variation in yields from year to year. Double-crop soybean yields typically are much better as you move farther southeast in Kansas, often ranging from 20 to 40 bushels per acre.

A recent publication explores the potential yield of double-crop soybeans relative to full-season yield (Figure 2) and the most limiting factors affecting the yields for double-crop soybeans. The link to this article is: https://bookstore.ksre.ksu.edu/pubs/MF3461.pdf.

Grain Sorghum

Grain sorghum is another double crop option. Unlike soybeans, sorghum hybrids for double cropping should be earlier maturing hybrids. Sorghum development is primarily driven by the accumulation of heat units, and the double crop growing season is too short to allow medium-late or late hybrids to mature before the first frost in most of Kansas.

Seeding rates and row spacing. Late-planted sorghum likely will not tiller as much as early plantings and can benefit from slightly higher seeding rates than would be used for sorghum planted at an earlier date. Narrow row spacing is advised, especially if the outlook for rainfall is good.

Fertilizer considerations. A key component for the estimation of N application rates is the yield potential. This will largely determine the N needs. It is also important to consider potential residual N from the wheat crop. This can be particularly important when wheat yields are lower than expected. In that situation, additional available N may be present in the soil. Assess the amount of profile N by taking soil samples at a depth of 24 inches and submitting them for analysis at a soil testing laboratory.

Double crop sorghum planted into average or greater-than-average amounts of wheat residue can result in a challenging amount of residue to deal with when planting next year’s crop. Nitrogen fertilizer can be tied up by wheat residue, so use application methods to minimize tie-up, such as knifing into the soil below the residue.

Weed control. Weed control can be important in double-crop sorghum. Warm-season annual grasses, such as crabgrass, can reduce double-crop sorghum yields. Using a chloroacetamide-and-atrazine pre-emergence product may be key to successful double-crop sorghum production. Herbicide-resistant grain sorghum varieties will allow the use of imazamox (Imiflex in igrowth sorghums) or quizalofop (FirstAct in DoubleTeam grain sorghum) that can control summer annual grasses.

No-till studies at Hesston documented 4-year average double crop sorghum yields of 75 bushels per acre compared to about 90 bushels per acre for full-season sorghum. A different 10-year study that did not have double crop planting but did compare early- and late-planting dates averaged 73 bushels per acre for May planting vs. 68 bushels per acre for June planting.

Sunflowers

Sunflowers can be a successful double crop option anywhere in the state, provided there is enough moisture at planting time to get a stand. Sunflowers need more moisture than any other crop to germinate and emerge because of the large seed. Therefore, stand establishment is important. Planting immediately after wheat harvest on a limited irrigation field can be a good fit to help with stand establishment.

Seeding rates and hybrid selection. When double-cropping sunflowers, producers should use similar seeding rates to what is typical for the area for full-season sunflowers. While full-season sunflowers can be successful in double-crop production, utilizing shorter-season hybrids can increase the likelihood of the sunflowers blooming and maturing before a killing frost.

Weed control. First, it is important to check the herbicide applications on the wheat. The rotation restriction to sunflowers after several commonly used wheat herbicides is 22-24 months.

Weed control can be an issue with double-crop sunflowers since herbicide options are limited, especially post-emergence. Thus, controlling weeds prior to sunflower planting is critical and may be complicated pre-plant restrictions for some herbicides. Planting Clearfield or ExpressSun sunflowers will provide additional post-emergence herbicide options, but ALS-resistant kochia and pigweeds still won’t be controlled. Imazamox (Beyond in Clearfield sunflower) has activity on small annual grasses as well as many broadleaf weeds, if they are not ALS-resistant.

Summer annual forages

With mid-July plantings, and where herbicide carryover issues are not a concern, summer annual sorghum-type forages are also a good double crop option. A study planted July 21, 2008 near Holton, when summer rainfall was very favorable, provided yields of 2.5 to 3 tons dry matter/acre for hybrid pearl millet and sudangrass at the low end to 4 to 5 tons dry matter/acre for forage sorghum, BMR forage sorghum, photoperiod sensitive forage sorghum, and sorghum x sudangrass hybrids. Earlier plantings may produce even more tonnage, as long as there is adequate August rainfall.

One challenge with late-planted summer annual forages is getting them to dry down when harvest is delayed until mid- to late-September. Wrapping bales or bagging to make silage are good ways to deal with the higher moisture forage this late in the year.

Corn

Is double-crop corn a viable option? Corn is typically not recommended for late June or July plantings because yield is usually substantially less than when planted earlier.

Typically, mid-July planted corn struggles during pollination and seldom receives sufficient heat units to fill grain before frost. Very short-season corn hybrids (80 to 95 RM) have the greatest chance of maturing before frost in double crop plantings, but generally have less yield potential when compared to hybrids of 100 RM or more used for full-season plantings. Short-season hybrids often set the ear fairly close to the ground, increasing the harvest difficulty. Glyphosate-resistant hybrids will make weed control easier with double crop corn, but problems remain present with late-emerging summer weeds such as pigweeds, velvetleaf, and large crabgrass. Keep in mind, corn is very susceptible to carryover of most residual ALS herbicides used in wheat.

Considerations for altering seeding rates and variety/hybrid maturity for the crops discussed above are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Seeding rate and variety/hybrid relative maturity considerations for double crops compared to full-season.

| Crop | Seeding rate | Relative maturity |

| ???????? Difference between double crop and full-season ???????? | ||

| Soybean | Increase | No change or longer |

| Sorghum | Increase | Shorter |

| Sunflower | No change | Shorter |

| Corn | No change | Shorter |

Volunteer wheat control

One of the issues with double cropping that is often overlooked by producers is the potential for volunteer wheat in the crop following wheat. If volunteer wheat emerges and goes uncontrolled, it can cause serious problems for nearby wheat fields in the fall as a host for the wheat streak mosaic complex of viruses [wheat streak mosaic (WSMV), High Plains disease (HPD), and triticum mosaic (TriMV)] that are transmitted by the wheat curl mite (WCM).

Volunteer wheat can generally be controlled fairly well with glyphosate or Group 1 herbicides such as quizalofop (Assure II, others), clethodim (Select Max, others), or sethodydim (Poast Plus, others), but control is reduced during times of drought stress. Atrazine can provide control of volunteer wheat in double-crop corn or sorghum, but control can be erratic depending on rainfall patterns.

For more detailed information about herbicides, see the “2025 Chemical Weed Control for Field Crops, Pastures, and Noncropland” guide available online at https://www.bookstore.ksre.ksu.edu/pubs/CHEMWEEDGUIDE.pdf or check with your local K-State Research and Extension office for a paper copy. The use of trade names is for clarity to readers and does not imply endorsement of a particular product, nor does exclusion imply non-approval. Always consult the herbicide label for the most current use requirements.

To Subscribe to the KSU Agronomy E-Updates follow this link

https://eupdate.agronomy.ksu.edu/index_new_prep.php

Authors contributing to the post

Sarah Lancaster, Weed Management Specialist

slancaster@ksu.edu

John Holman, Cropping Systems Agronomist

jholman@ksu.edu

Logan Simon, Southwest Area Agronomist

lsimon@ksu.edu

Tina Sullivan, Northeast Area Agronomist

tsullivan@ksu.edu

Jeanne Falk Jones, Multi-County Agronomist

jfalkjones@ksu.edu

Boosting Wheat Grain Protein: Smart Spray Strategies for Better Grain Quality

Brian Arnall, Precision Nutrient Management Specialist

Samson Abiola, PNM Ph.D. Student.

Wheat Protein and Technology challenge

For wheat growers, achieving both high yields and good protein content is a constant challenge. Wheat contributes about 20% of the world’s calories, making it a vital crop for global nutrition. Every season, we face the question of how to boost grain protein concentration (GPC) without sacrificing the yield.

Traditional approaches often involve applying more nitrogen (N) early in the season. While this can help, it is often wasteful, environmentally problematic, and does not always translate to higher protein levels at harvest. The effectiveness of N applications depends not just on timing but also on the spray technology used, including the N source, nozzle type, and droplet size. While protein premiums are never guaranteed, we wanted to develop recommendations prior to the need.

The Research Approach: Timing and Technology

Our research team conducted a comprehensive three-year study (2019-2022) across three Oklahoma locations (Perkins, Lake Carl Blackwell, and Chickasha) to investigate how different combinations of N sources, nozzle types, and droplet sizes affect protein when applied during flowering. We considered two N sources (urea-ammonium nitrate (UAN) and aqueous urea [Aq. Urea]). We also evaluated three nozzle types: Standard flat fan (FF) nozzles with a traditional 110° spray angle, 3D nozzles with three-dimensional spray patterns that enhance canopy penetration, Twin (TW) nozzles with dual forward and rear facing sprays (30° forward and backward)

Finally, we tested both fine droplets (below 141 microns) and coarse droplets (≥141 microns). All applications were made at flowering i.e., when you start seeing yellow anthers sticking out of the wheat heads. Both UAN and Aq. urea were applied at a 20 gpa application rate with a 1:1 dilution with water delivering approximately 30 lbs. of N per acre.

What We Found: More Protein Without Hurting Yield

The big news? Spraying N at flowering boosted wheat protein by 12% without sacrificing yield. This held true across fields yielding anywhere from 30 to 86 bushels per acre. Why doesn’t it hurt yield? By flowering time, your wheat has already “decided” how many heads and kernels it will produce. The N you spray at this stage goes straight to building protein in those existing kernels.

One important caution: Mother Nature still calls the shots, so keep an eye on the forecast before planning your application. If the weather is hot and dry, this is not a good idea. First, those environments typically result in higher protein anyways. But low humidity will significantly increase the likelihood of burn.

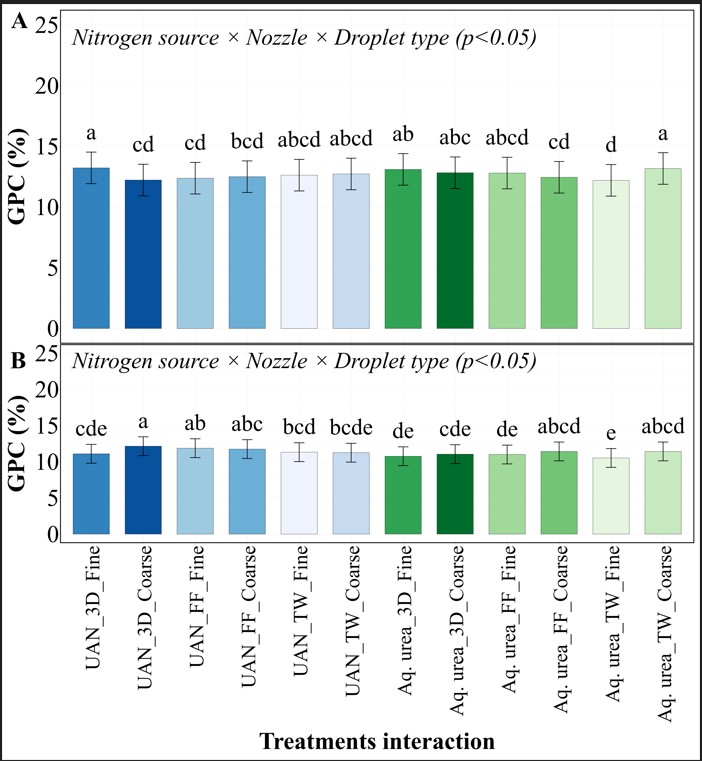

Lake Carl Blackwell Findings: UAN Takes the Lead

At our Lake Carl Blackwell site, we saw our highest protein levels reaching up to 16.3% in some plots. In 2020-21, UAN clearly beat Aq. urea (14.7% vs. 14.0% protein). Both were much better than not applying any N at flowering (13.1%) (Figure 1A). Also, the 3D nozzle gave us the highest protein (14.7%), outperforming the control but performing similarly to FF (14.0%) and TW nozzles (14.2% (Figure 1B). The next year (2021-22) showed us something interesting, the combination of N source and droplet size really matters. UAN with fine droplets hit 14.6% protein, similar to UAN with coarse droplets (14.4%) and Aq. urea with coarse droplets (14.3%), but Aq. urea with fine droplets fell behind at just 13.8% (Figure 1C).

Chickasha Results: Matching Your N to the Right Droplet Size

At Chickasha, protein ranged from 10.1% to 13.8% across the two years we studied. In 2021-22, UAN beat Aq. urea (12.7% vs. 12.2%), and both beat the control (11.8%) (Figure 2A). Also, the 3D nozzle (12.8%) outperformed both FF and TW nozzles (both 12.2%) (Figure 2B).

In 2020-21, we found that the combination of N source, nozzle type, and droplet size all worked together to affect protein. The winning combination was UAN with 3D nozzle and fine droplets (13.23% protein), which performed similarly to Aq. urea with TW nozzle and coarse droplets (13.18%) (Figure 2C). The least performer was Aq. urea with TW nozzles and fine droplets (12.20%) among the treatments. This shows how weather and growing conditions can change which factors matter most from year to year

Perkins Results: Getting Every Detail Right

At our Perkins site, we saw protein levels ranging from 10% to 13.1%. Here, the combination of all three factors (N source, nozzle type, and droplet size) made a huge difference. The best setup was UAN with 3D nozzle and coarse droplets (12.2% protein). The worst was Aq. urea with TW nozzle and fine droplets (10.5%) (Figure 3). That’s a 15% difference that could mean the difference between premium and feed-grade wheat!

UAN consistently outperformed Aq. Urea across all setups. For example, UAN with 3D nozzle and coarse droplets produced 10% higher protein than the same setup with Aq. Urea.

Equipment and Application Recommendations

Over the three years UAN consistently outperformed perform Aq. urea, showing there is no need for a special formulation and that commercially available UAN is all we really need as a source. While no nozzle type significantly stood out across all sites the 3-D nozzle did show up a couple times as being statistically better. So the important message would be that while the high tech nozzles could provide some value the traditional flat fan performed quite well. While some differences were seen in droplet size, the lack of consistency leads us to say focus on good coverage with limited drift.

Take-Home Messages

- Foliar N at flowering boosted wheat protein by 12% without affecting yield multiple growing seasons and locations. This increase was from 0.5 to nearly 2.0 % protein.

- Nitrogen source matters – UAN consistently outperformed Aq. Urea.

- Your spray technology mattered but not lot – and 3D nozzles generally gave the best results. The good ole flat fans nozzles still did quite will.

- Match droplet size to your setup – generally fine for UAN and coarse for Aq. Urea.

- This targeted approach enhances grain quality without sacrificing yield, potentially improving grain prices and profitability while using N more efficiently.

- Mother Nature still calls the shots, so keep an eye on the forecast before planning your application. If the weather is hot and dry, this is not a good idea. First, those environments typically result in higher protein anyways. But low humidity will significantly increase the likelihood of burn.

This blog was written based upon the data published in the manuscript “Optimizing Spray Technology and Nitrogen Sources for Wheat Grain Protein Enhancement” which is available for free reading and downloading at https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0472/15/8/812

Any questions or comments feel free to contact me. b.arnall@okstate.edu

Nitrogen and Sulfur in Wheat

Brian Arnall, Precision Nutrient Management Specialist

Samson Abiola, PNM Ph.D. Student.

Nitrogen timing in wheat production is not a new topic on this blog, in-fact its the majority. But not often do we dive into the application of sulfur. And as it is top-dressing season I thought it would be a great opportunity to look at summary of a project I have been running since the fall of 2017 which the team has call the Protein Progression Study. The objective was to evaluate the impact of N and S application timings on winter wheat grain yield and protein. With a goal of looking at the ratio of the N split along with the addition of S and late season N and S, in such a way that we could determine BMP for maximizing grain yield and protein.

My work in the past has shown two things consistently, that spring N is better on the average and S responses have been limited to deep sandy soils in wet years. Way back when (2013) on farm response strips showed high residual N at depth and no response to S. https://osunpk.com/2013/06/28/response-to-npks-strips-across-oklahoma/. But there has been a lot of grain grown since that time expectations are that we should/are seeing an increase in S response. In fact Kansas State is seeing more S response, especially in the well drained soils in east half of the state.

Some KSU Sulfur works.

https://www.ksre.k-state.edu/news/stories/2022/04/video-sulfur-deficiency-in-wheat.html

https://eupdate.agronomy.ksu.edu/article/sulfur-deficiency-in-wheat-364-1

Click to access sulphur-in-kansas-plant-soil-and-fertilizer-considerations_MF2264.pdf

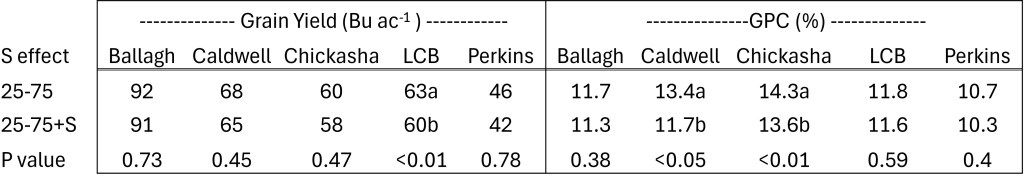

So the Protein Progression Project was established in 2017 and where ever we had space we would drop in the study. So in the end across six seasons we had 13 trials spread over five locations. Site-years varied by location: Chickasha (2018-2022), Lake Carl Blackwell (2018-2023), Ballagh (2020), Perkins (2021), and Caldwell (2021).

First lets just dive into the the N application were we looked at 100% pre vs 50-50 split and 25-75 split (Table 2.) Based upon the wealth of previous work https://osunpk.com/2022/08/26/impact-of-nitrogen-timing-2021-22-version/, its not much of a surprise that split application out preformed preplant and that having the majority applied in-season tended to better grain yields and protein values.

This next table is were things get to be un-expected. While the data below is presented by location, we did run each site year by itself. In no one site year did S statistically, or numerically increase yield. As you can see in Table 2 below, the only statistical response was a negative yield response to S. And you can not ignore the trend that numerically, adding S had consistently lower yields. Even more surprising was the same trend was seen in Protein.

One aspect of Protein Progression trials were that while 0-6″ soil test S tended to be low. We would often find pretty high levels of S when we sampled deeper, especially when there was a clay increase with depth. Sulfur tends to be held by the clay in our subsoil. We are also looking at better understanding the relationship between N and S. In fact a review article published in 2010 discussed that the N and S ratio can negative influence crop production when either one of the elements becomes un-balanced. For example we are seeing more often in corn that when N is over applied we can experience yield loss, unless we apply S. Meaning at 200 lbs of N we make 275 BPA, at 300 N lbs we make 250, but 300 N plus 20 S we can make 275 again. Part of the rationale is that excessive N limits S mineralization. On the flip side if S is applied while N is deficient and yield decrease could be experienced. Maybe that is what we are seeing in this date. Either way, this data is why the Precision Nutrient Management program is spending a fair amount of efforts in understanding the N x S relationship in wheat (which we are looking at milling quality also) and corn.

A quick dive into increasing protein with late N applications. At three of the five location GPC was significantly increased with Late N. In most cases the anthesis (flowering) application was the highest with exception of Caldwell. We will have another blog coming out in a month that digs into anthesis applied N at a much deeper level, looking at source, nozzle and droplet sizes.

Looking at this study in a vacuum we can say that it probably best to split apply your N and that in central and northern Ok the addition of S in rainfed wheat doesn’t offer great ROI. If I look at the whole picture of all my work and experience I would offer this. For grain only wheat, the majority if not all N should be applied in-season sometime between green up and two weeks after hollow stem. I have had positive yield responses to S applied top-dress, but it has always been deep sandy soils and wet seasons. I have not have much is any response to S in heavier soil, especially if there is a clay increase in the two feet of profile. So my general S recommendation is 10 lbs in sandy soils and if you show low soil test S in heavier ground and you are trying to push grain yields, then you could consider the addition of S as a potential insurance. That said, I haven’t seen much proof of it.

Take Homes

* Split application of nitrogen resulted in higher grain yields and protein concentrations when compared to 100% preplant.

* Putting on 75% of the total N in-season tended to result in higher grain yields and protein concentrations when compared to 50-50 split.

* Adding 10 lbs of S topdress did not result in any increase in grain yield or protein.

A big Thanks to the collaborators providing on-farm locations for this project. Ballagh Family Farms, Turek Family Farms and Tyler Knight.

Citation. Jamal, A.,*, Y. Moon, M. Abdin. 2010 Review article. Sulphur -a general overview and interaction with nitrogen. AJCS 4(7):523-529 (2010). ISSN:1835-2707.

Any questions or comments feel free to contact me. b.arnall@okstate.edu

A comparison of four nitrogen sources in No-till Wheat.

Jolee Derrick, Precision Nutrient Management Masters Student.

Brian Arnall, Precision Nutrient Management Specialist.

Nitrogen (N) fertilizer’s ability to be utilized by a production system is reliant upon the surrounding environment. The state of Oklahoma’s diverse climate presents unique challenges for producers aiming to apply fertilizers effectively and mitigate the adverse effects of unfavorable conditions on nitrogen fertilizers. To lessen the effect that unfavorable environments can have on N fertilizers, chemical additions have been introduced to base fertilizers to give the best possible chance at an impact. With that in mind, a study was conducted to investigate the impact of N sources and application timings on winter wheat grain yield and protein, aiming to identify both the agronomic effects of these sources and how variations in their timing may influence the crop. Included below is a figure of where and when the trials were conducted.

In each of the trials, four N sources (Urea, SuperU, UAN, and UAN + Anvol) were analyzed across a range of timings. The sources were categorized on two criteria: application type, distinguishing between dry and liquid sources, and the presence of additives versus non-additives. The two N sources were Urea and UAN. The other products in this study were SuperU and Anvol. SuperU is a N product that has Dicyandiamide (DCD) and N- (n-butyl) thiophosphoric triamide (NBPT) incorporated into a Urea base. Anvol is an additive product which contains NBPT and Duromide and can be incorporated with dry or liquid N sources.

For additional clarification, N- (n-butyl) thiophosphoric triamide is a urease inhibitor which prevents the conversion of urea to ammonia. Duromide is a molecule which is intended to slow the breakdown of NBPT. DCD is a nitrification inhibitor that slows the conversion of ammonium to nitrate.

Urea is a stable molecule which in the presence of moisture is quickly converted to stable ammonium (NH4), however it can be converted to ammonia gas (NH3) by the enzyme urease beforehand. Additionally, when urea is left on the soil surface and not incorporated via tillage or ½ inch of a precipitation event, the NH4 that was created from urea can be converted back to NH3 and gasses off. So, the use of urease inhibitors is implemented to allow more time for incorporation of the urea into the soil.

Ammonium in the soil is quickly converted to nitrate (NO3) by soil microbes when soil temperature is above 50F°. When N is in the NO3 form it is more susceptible to loss through leaching or denitrification. Therefore, nitrification inhibitors are applied to prevent the conversion of NH4 to NO3.

All treatments were applied at the same rate of 60 lbs of N ac-1, which is well below yield goal rate. A lower N rate was chosen to allow the efficacy of the products to express themselves more clearly, rather than a higher rate that may limit the ability to determine differences between product and rate applied. Furthermore, dry N sources were broadcasted by hand across the plots while liquid sources were applied by backpacking utilizing a handheld boom with streamer nozzles. Application timing dates were analyzed by identifying the growing degree days (GDD) associated with each timing which were correlated with the Feekes physiological growth chart displayed in Figure 3. Over the span of the study, N has been applied over six stages of growth. The range of application dates stems from the fact that it is difficult to get across all the ground exactly when you need to.

Over four years this study was replicated 11 times. Of those 11 site years, three did not show a response to N, so they were removed from further analysis. The graph above shows the average yield of each respective source (across all locations and timings). The data shows there is a statistical difference between SuperU and Urea vs. UAN, but no statistical difference between UAN treated Anvol and any other source. The data indicates that on average, a dry source resulted in a higher yield than when a liquid source was applied. This makes sense considering that in many cases, wheat was planted in heavy residue during cropping seasons that experienced prolonged drought conditions. Therefore, it is thought that a liquid source can get tied up in the residue. This was first reported in a previous blog posting, Its dry and nitrogen cost a lot, what now?, and years later, the same trends in new data indicate the same conclusion.

If we look at all timings and site years averaging together there is no statistical difference between a raw N source and its treated counterpart. This result is not surprising as we would expect that not all environments were conducive to loss pathways that the products prevented. Basically, we would not expect a return on investment in every single site year, and therefore you do not see broad sweeping recommendations. There was a 2-bushel difference between UAN and UAN Anvol. As this was a numerical difference, not a statistical one, I would say that while the yield advantage was not substantial there may be economic environments that would suggest general use.

While the evaluation of the four sources across all timings and locations showed some interesting results, this work was performed to see if there was a timing of application which would have a higher probability of a safened N returning better yields. As you look at the chart above it is good to remember the traditional trend for precipitation in Oklahoma, where we tend to start going dry in November and stay dry through mid-January. Rain fall probability and frequency starts to increase around mid-February, but moisture isn’t consistent until March. This project was performed during some of the dryest winters we have seen in Oklahoma. Also, just a note, since the graph above combines all the sites that have differing application dates the absolute yields are a bit deceiving. For example, the Nov and Feb timings include the locations with our highest yields 80+ bpa per acre, while January and February include our lowest. So, the way this data is represented we should not draw conclusions about best time for N app. For that go read the blogs Impact Nitrogen timing 2021-2022 Version and Is there still time for Nitrogen??

Figure 6a and b. A: The mesonet rainfall totals for Oct -Dec for the Lake Carl Blackwell research station for 2020-2023 A: The mesonet rainfall totals for Jan – April for the Lake Carl Blackwell research station for 2021-2024. The black line on both graphs is the 10 year average.

Now about the source by time. While it’s not always statistical you can see that the dry sources tend to outperform the liquid sources at most timings. Also, while there is never a statistical difference in the raw product and safened, there are trends. SuperU tended to have higher yields than urea when applied in Nov and Dec. It could be hypothesized that the addition of a nitrification inhibitor may have added value, however the UAN + Anvol in November also showed a positive response that would point to the value being derived from urease inhibition. As we move into the period of more consistent rainfall the differences between products start declining, which also makes sense.

The following figures illustrate rainfall events following N application, with the application dates indicated by arrows. Figure 7 corresponds to our trial conducted in 2020-2021, which revealed no statistical differences among the N sources for any timing. However you can see that for the first timing (orange bars) which received 0.7″ of rain two days after application that the yields are uniform than the grey bars with both safened products are numerically greater than the raw product, just makes since as a 0.1″ precipitation event happened 6 days application application and it wasn’t until day 9 that a good incorporating rainfall occurred.

Figure 8 has data the same location one year later, during which we observed statistically significant differences among the dry and liquid N sources. The environmental conditions during 2022 were drier, impacting the incorporation of N applications. The lack incorporating rainfall likely led to tie-up of the UAN on/in the residue, limiting access to plant available N.

It is essential to highlight the environmental conditions encountered throughout this project. From 2020 to 2023, moderate to extreme drought conditions were prevalent. During this period, the influence of a La Niña led to reduced moisture availability. For the first time in an extended period, the 2023-2024 wheat year began under a strong El Niño, which typically results in increased moisture accumulation compared to its La Niña counterpart. Currently, there are indications that a return to a La Niña system may occur by the end of the year, raising the expectation of a potential reversion to drought conditions. Consequently, this research may provide producers with options to consider regarding sources of N application in their production systems.

We plan to update this blog with a deeper analysis of the results seen at each location as soon as possible. But for now, we wanted to share the early look.

At this point the reason for the liquid yield gap is speculation. It could be increased loss via ammonia volatilization or it could be immobilization of the N by microbes. The next step of this process is to understand 1) is the UAN tied up in the residue via immobilization via microbes or is it lost to volatilization. 2) If tied up, what is the time frame between application and immobilization.

Take Home:

- It was observed that during low moisture conditions, dry N sources had significantly better results than liquid counterparts in no-till winter wheat production.

- On average, additive products had no significant impact on grain yield versus base fertilizers, however, when evaluated by location, differences could be found. Responses usually correlated with post-application weather conditions.

- When adequate precipitation was received shortly after application, N sources did not show differences.

Any questions or comments feel free to contact me. b.arnall@okstate.edu

In-Furrow Placement of Urea Products with Wheat Seed

Its that time of year I always get the question of “How much urea can I put in the furrow?”. My answer is always two fold first, I wouldn’t recommend it, its a risky venture. Even though I know some do it. Second, my research shows very little is any value from N in furrow. I like P but N just doesn’t show me any return. So for me the process is high risk, with little or no potential for return. But with blog I turn to our purple friend up north to share what their research has sown.

Brian

Guest Authors Kansas State University

Lucas Haag, Agronomist-in-Charge, Southwest Research-Extension Center, Tribune lhaag@ksu.edu

Alan Schlegel, retired

Dorivar Ruiz Diaz, Nutrient Management Specialist ruizdiaz@ksu.edu

To save time and cost, some wheat producers may be thinking about adding a little extra nitrogen (N) as urea or UAN to their phosphorus fertilizer through the drill with the seed. This would either be in addition to, or instead of, any preplant N applications.

While a minimum preplant N application of 20 to 40 lbs N per acre is often desirable, especially in no till production systems, there are risk involved when placing urea containing fertilizers in direct seed contact. Traditionally, we have suggested that no urea or UAN solution be placed in contact with the seed. With the continued adoption of air-seeders a common question we receive from producers is can urea, or enhanced urea products be placed in-furrow.

Methods of early-season nitrogen applications

If the starter fertilizer can’t be “spiked” with urea to add extra N, how can the necessary 20 to 40 pounds of N be applied? Subsurface banding (knifing) of N as either anhydrous ammonia, liquid UAN, or dry product will result in the greatest N use efficiency by the wheat crop. This is especially true for no-till wheat production.

If knifed N applications are not used, the next best application method would be surface banding (dribbling) of UAN solution in streams on 15- to 18-inch centers. Broadcasting urea, ammonium nitrate, or UAN applications are not generally as efficient as subsurface banding, but they are often the best choice due to equipment, logistics, or weed management considerations. Broadcast applications of N will have the most consistent performance if followed by light incorporation, precipitation, or irrigation.

Direct seed placement of nitrogen

When placing starter fertilizer in direct contact with wheat seed, producers should use the following guidelines:

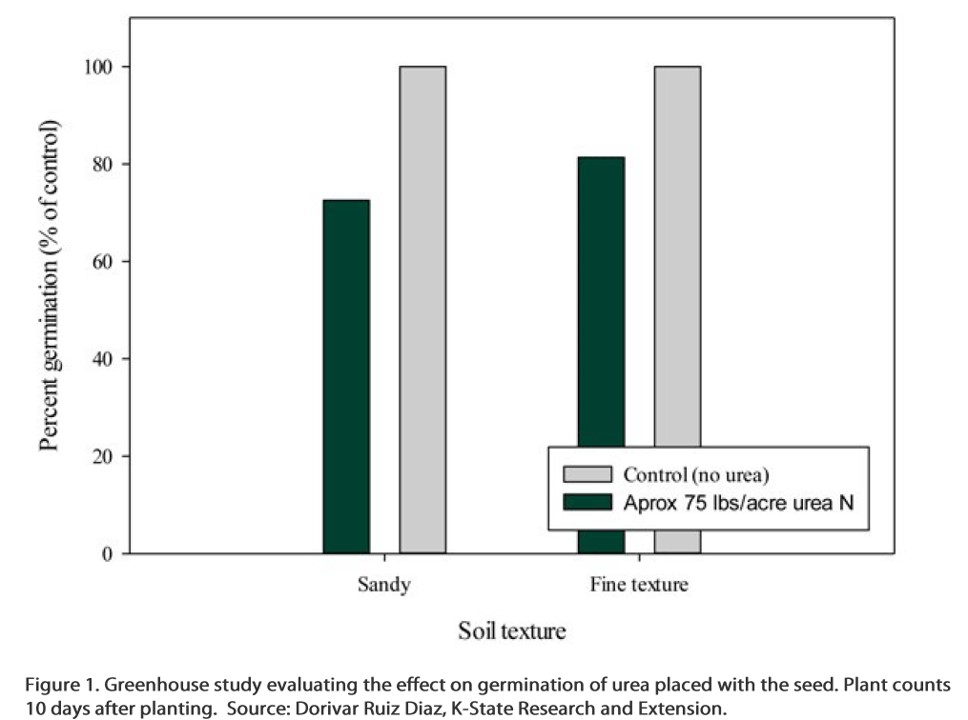

The problem with placing urea-containing fertilizer with the seed is that urea is initially converted to ammonia and may be toxic to plant roots if the wheat seed is placed in direct contact with the fertilizer. Producers may hear of someone who has placed urea in direct seed contact and seemed to have no problems, but there are also many cases where urea-containing N fertilizers has injured the developing seedling and reduced or delayed emergence significantly. The risk of injury is greater in drier soils, at higher soil pH levels, and at higher N rates. High soil pH favors a higher concentration of ammonia as compared to ammonium as urea hydrolyzes. There is significant risk associated with placing urea-containing fertilizers in direct seed contact.

The chart below shows how soil texture affected the level of wheat germination when urea-N was applied with the seed in a K-State greenhouse study. The wheat was well watered in this study, but urea-N placed with the seed still reduced germination, especially in the sandy soil. The readings shown below were taken after 10 days. With the high rates of urea used in this study, it is possible that more damage to the seedlings would occur with time as the urea continues to hydrolyze into ammonia.

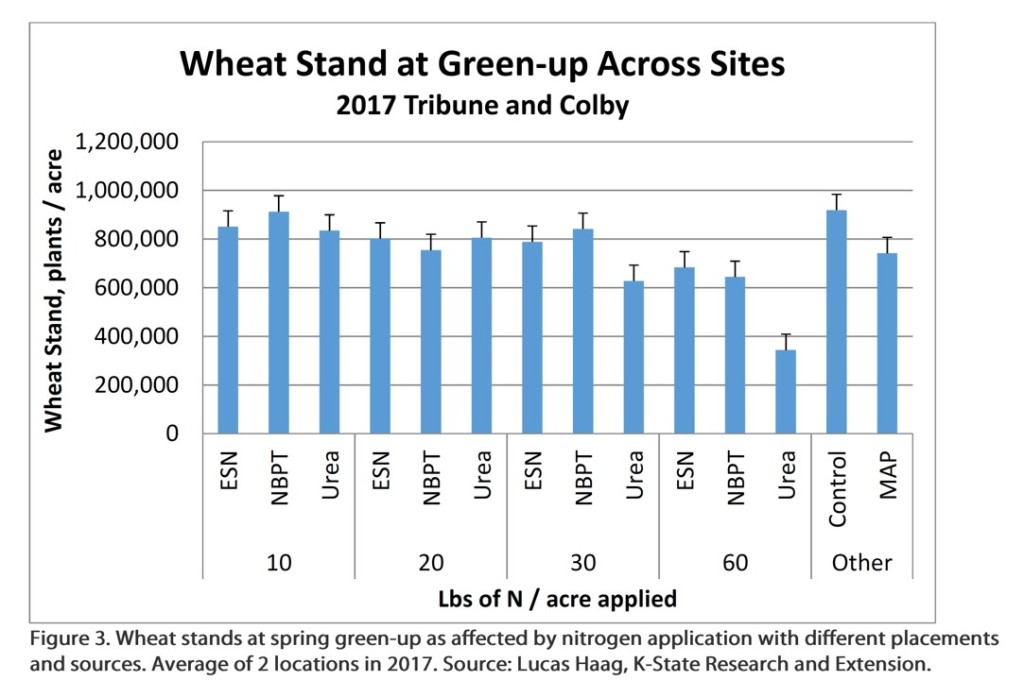

Field studies have also shown reduced wheat stands due to in-furrow placement of urea. Across 5 site years in western Kansas the placement of urea in-furrow has resulted in decreased stands at spring greenup compared to the control (Figure 2).

The stand reduction becomes especially noticeable at higher rate of N. One of the challenges of understanding the risk of seedling injury is that the magnitude of injury varies by field conditions an years. In some years very little reduction may be evident, even at higher rates of N, while in other years, stand reductions (and their associated impact on yield) is very evident. As an example at Tribune in 2017, reduction in stand caused by urea placement with seed, and their effect on yield were quite evident (Figures 3 and 4).

Stands were reduced 32 and 63% compared to the control when 30 and 60 lbs of N as urea were applied in-furrow (Figure 3). This resuled in yield reductions of 14 and 40%, respectively (Figure 4).

If you’d like to apply extra N directly in the seed furrow, one option is to use a controlled-release form of N, such as ESN. As shown in figure 4, at N application rates of 30 lbs/ac and less, where ESN-N was applied in-furrow, wheat yields were essentially the same as where the N was applied pre-plant, and higher compared to the same amount of N applied as urea. At the highest rate of application in the study, 60 lbs/ac, even ESN resulted in stand and grain yield reductions.

Also, air seeders that place the starter fertilizer and seed in a band an inch or two wide, or side band the fertilizer relative to the seed, provide some margin of safety because the concentration of the fertilizer and seed is lower in these diffuse bands. In this scenario, adding a little extra urea containing N fertilizers to the starter less likely to injure the seed – but it is still a risk.

Here is a great video by Dr. Haag.

How do you handle your soil sample….

It’s that time of year where wheat producers are in all stages of prep across the state, the graze out folks are wondering when the rains will hit to get the dusted in wheat up and the grain only folks are prepping grain drills or dealing with summer crop harvest. While this blog is focused on the wheat producers it should be acknowledged as a work of caution for anyone who pulls soil samples in environments where the temps during sampling can be above the mid 80’s.

Following some fantastic work by our Wild Cat Soil Fertility Counterparts (see blog) we dug into the same question of how does soil sample handling post collection impact the results. Dr. Ruiz-Diaz results on the impact of storage on nitrogen values was not surprising. But we wanted to go the next step and add in sample bag type.

Our Project

We collected a soil ground and homogenized. Placed in three types of bags Ziploc, Commercial (resin lined paper that is closed) and SWFAL bag (breathable material). Placed samples in a mini-van (Field) and brought a group onto campus (Office). With both sets of samples we had temperature loggers collecting hourly data. Every three days we collected four samples from each location determined moisture content and ran a full spectrum soil analysis including CO2 burst. The soil we used had a OM of 1.1% and soil pH of 6.1

Now let’s back up. Why was the KSU data not surprising. Well for those certified and honorary nitrogen ninjas we understand that the N-cycle processes of mineralization, immobilization, and nitrification are biological reactions which are significantly impacted by soil moisture and soil temperature. But the short and quick version is that the microbes that convert organic N to mineral N (NH4) and convert NH4 to NO3 like warm conditions with good soil moisture. So, when you pull soil samples, hopefully there is some moisture in the soil and then you place it in a bag and seal it. This creates an effective greenhouse environment where moisture cannot escape and is the perfect place for microbes to microbial things. Therefore, you expect the organic cycle and nitrogen cycle to move and move quickly through the processes of mineralization, ammonification, and nitrification.

Back to the data.

First, we have the average daily temperatures from the sitting vehicle and the lab. On days 2-5 the average temp of the van was over 100°, after that the temps dropped. One thing to remember is the temp of the van is an average of a wide-ranging highs and lows between morning and midday while the office temperature being stable throughout the entire day.

What is the most interesting and revealing data may be the soil moisture of the samples. Unfortunately, day 3 samples went straight to the oven, but you can see by day 6 the SFWAL bags (yellow line) had dried significantly while it wasn’t until day 27 did the Commercial bags in the van (Black line w/ triangle) show signs of drying. It’s also important to note that while there are two lines (Field and Office) for the Commercial bags and Ziploc bags, but only one for the SWFAL bags. That is because for all variables measured there was never a significant difference between the SWFAL Field value and the SWFAL Office value.

We are going to start off with the variable that changed the most, NO3-N. This is also the form of N that is measured in most soil test. With a starting point of 3.4 lbs. N ac-1 (based on a six inch soil sample depth) by day 6 the Field samples had jumped to 15.6 lbs. The office samples had much slower increase in NO3 with it taking 9 days to reach 10 lbs. You can also see that the error bars start showing up in the samples after about two weeks. The bars show the range in the sample results of a treatment. The interesting thing we saw was that the location within the van was significant. We set each replication of samples in a different spot in the van, the front seat, middle seat, and rear. The thermometers set with each replications showed that each area of the van had slightly differing temperature, which in turn affected the samples.

Ammonium (NH4-N), which is only reported by a few labs is also impacted by the storage location and bag type, however not to the sample level as NO3-N. Effectively the SWFAL bags and all samples taken to the office maintained consistent NH4 levels. The Com bag and Ziplocs left in the van however saw a significant increase in NH4 over time, basically a 2 lb per day increase.

Of the other measured parameters such as potassium, sulfur, and CO2 burst data were effected. These will be discussed more in depth in a peer reviewed publication and factsheet.

Take Home’s from the Work

While the majority of the nutrients were relatively un affected by the bag type or storage those that are more heavily influenced by organic matter and biological activity where, this includes many of the soil health parameters. The use of SWFAL soil bags resulted in data that was not impacted by storage or time. While most clients of the OSU lab use these bags, more than one samples been brought into the county via a sealed Ziploc baggie. However the majority of the soil samples collected are placed into the resin lined paper bags and sealed. This data set is also important to those who use laboratories that run the Haney test which includes measures of NO3, NH4, Organic N, CO2 respiration and H2O extracted Organic C. It is critical that when using these type of bags that the samples be brought into climate controlled facilities as soon as possible. Its good to remember when looking at the data that the soil we used had a OM of 1.1%, initial NO3 of 3.4 lbs. and NH4 of 14 lbs. A soil with a higher OM% could have even greater change. Another viable is if the soil sample depth is greater than 6”. If your sample depth is 8” then the value is 33% higher.

Questions or comments feel free to reach out via email or social media.

Brian Arnall, Precision Nutrient Management b.arnall@okstate.edu

Did in-furrow starter products increase yields?

Bronc Finch, Precision Nutrient Management Post-Doctorial Scientist.

Brian Arnall, Precision Nutrient Management Specialist.

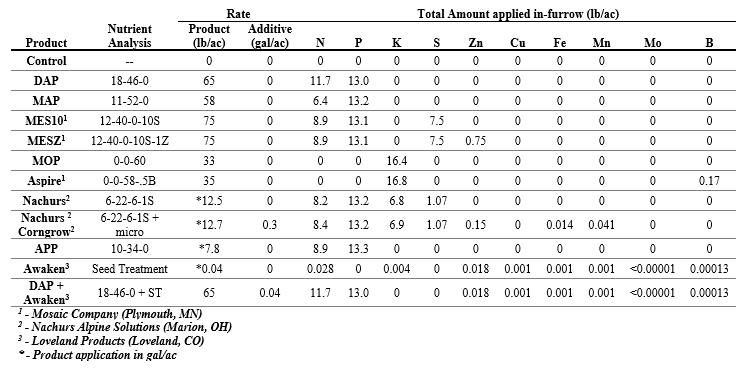

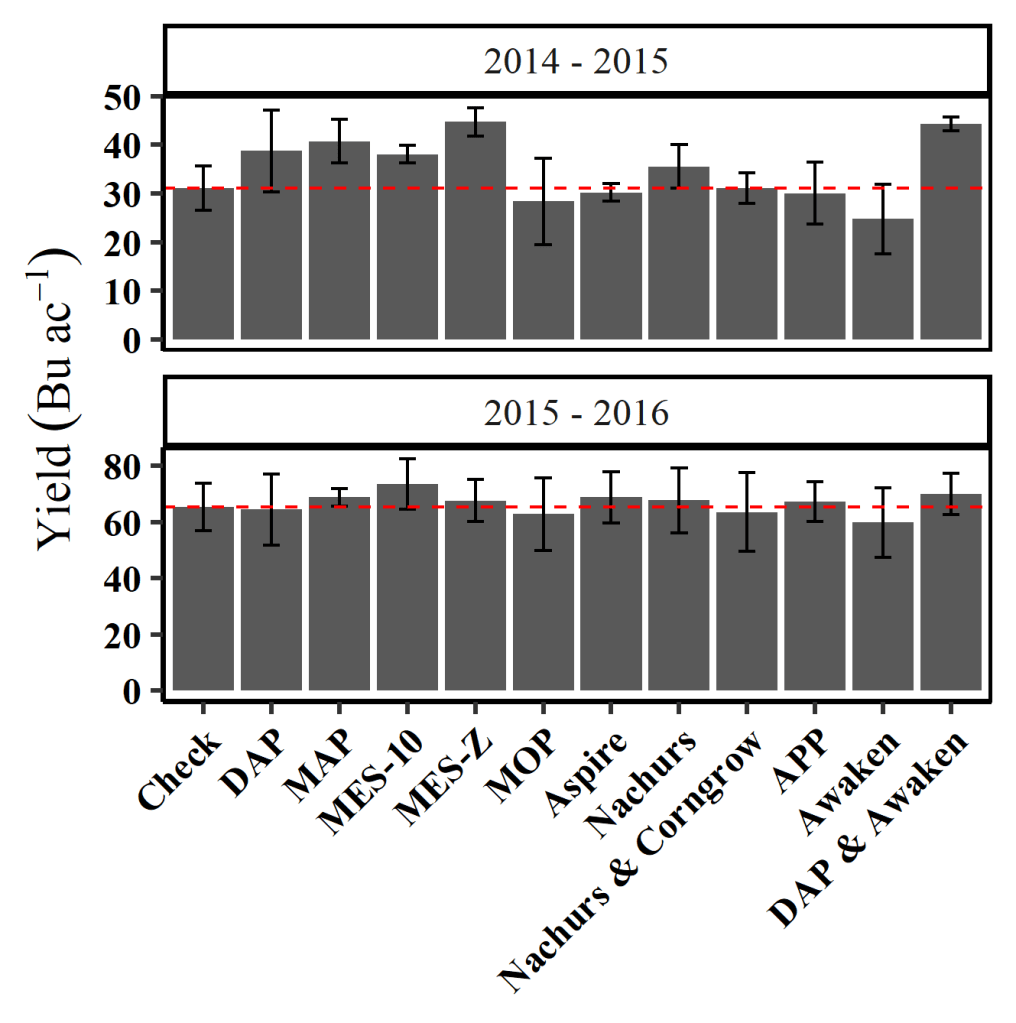

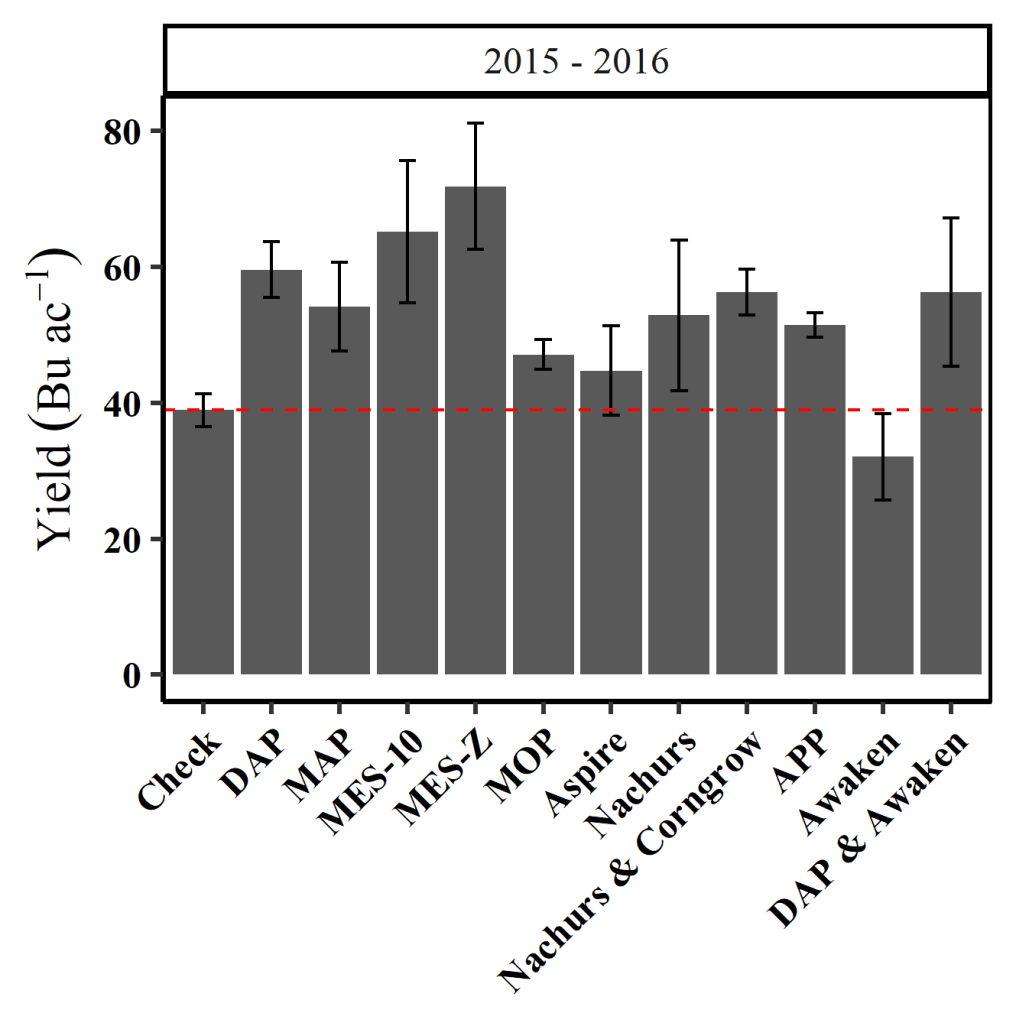

As winter wheat planting time approaches this question arises often when fertilizer decisions are being made. There are several products that have been marketed to wheat producers that contain combinations of nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) as well as some plant essential micro-nutrients. These products are designed to be placed with the seed as an in-furrow application at planting and provide nutrients earlier in the season than traditional dry spreading methods. While the state of Oklahoma macro-nutrient deficiencies are often corrected with traditional fertilizing methods and micro-nutrient deficiencies are not commonly witnessed in winter wheat; these products are often sold with the expectation yield increases can still occur. This has led to the question can these fertilizer products improve winter wheat yield production regardless of soil analysis results? To answer this Oklahoma State University developed a study evaluating eleven different starter fertilizer options available to producers (Table 1). Of these eleven fertilizer options three are commonly available fertilizers, and eight of them are products available through specific companies. The study was carried out at three locations a year for two years.

To compare the ability of these products to increase yield beyond the recommendation of soil test results, pre-plant soil samples were collected to a 6-inch depth at each of these research sites. Soil analysis of the five-site years used in this evaluation (Table 2) reported no deficiency at the Lake Carl Blackwell research farm. Deficient concentrations of P (< 32.5 ppm) was recorded at the North 40 research site and Perkins research station, along with a low pH (4.8) at the Perkins research station. Acidic soils are of concern for crop production having many detrimental impacts to root production, however there is also influence on nutrient availability. Aluminum concentrations are often higher in low pH soils which will result in root pruning and the binding of applied P, increasing the concerns when soil analysis P concentrations are already deficient.

Evaluation of these commercially available products at non-nutrient deficient sites show no influence of any in-furrow placed fertilizer product on winter wheat grain yield compared to an unfertilized check, yielding an average of 52 bu ac-1 in 2014-2015, and 93 bu ac-1 in 2015-2016 (Figure 1). Figure 1, along with the following figures, show the mean and variability of winter wheat grain yield of each of the commercially available starter fertilizer product treatments, as well as the check treatment which received no fertilizer application. The column for each treatment represents the grain yield in bu ac-1 which is the average of three replications the variability of grain yield at an individual treatment can be observed by the error bars which depict the range of grain yields within a specific treatment. The larger the error bar the less consistent the yield and the harder it is to separate out statistical differences in yield.

When the soil test P level was below 32.5 ppm, some P containing starter fertilizers where able to increase winter wheat grain yield in 2014-2015 growing season at North 40. Products containing 40 – 52% P; MAP, DAP + Awaken and MES-Z, improved grain yield by up to 14 bu ac-1 compared to the check. At the North 40 locations APP did not show the same increase in yields as DAP and MAP. The addition of micro-nutrients by Awaken combined with DAP yielded a 20 bu ac-1 increase over Awaken used alone, but no increase compared to DAP or MAP used alone. Similarly, the addition of Zinc by MES-Z yielded similar to the base product, MAP.

When P deficiency was compounded by a low pH such as observed at Perkins there was response to more in-furrow products. Compared to the check, increases up to 32 bu ac-1 in winter wheat grain yield was found by DAP, MES-10, MES-Z, Nachurs + CornGrow, and DAP + Awaken. Further investigation revealed the source of P fertilizer (DAP, MAP, and APP) reported no difference in yield averaging 55 bu ac-1. The addition of S and K by Nachurs was not different from APP, which is a similar liquid fertilizer, averaging 52 bu ac-1. Micro-nutrient additions by Awaken combined with DAP (56 bu ac-1), and by CornGrow combined with Nachurs (56 bu ac-1) did not increase winter wheat grain yield compared to each other or their respective base products of DAP (59 bu ac-1) and Nachurs (53 bu ac-1). Similarly, additions of S by MES-10 and S and Zn by MES-Z yielded similar to one another with 65 and 72 bu ac-1respectively but produced 14 bu ac-1 more yield on average than the base product MAP. At Perkins, which is a well-drained sandy loam soil, we often see a yield response to S when yield levels so seeing a response to the products that added 7 lbs of S, was not un-expected.

With these results in mind and the current cost of fertilizers, the addition of fertilizer products on non-limiting soils is not expected to result in an increase in winter wheat grain yield. Also, many of these products contain micro-nutrients that are rarely found to be at deficient levels for much of the winter wheat production region in Oklahoma. Therefore, the use of these products on non-nutrient limiting soils would unnecessarily increase the cost of production and decrease the return on investment. However, that is not to say these products should be avoided completely, in the event of a nutrient limiting soils some products show potential benefit for correct soil deficiencies. As observed some P containing products were able to provide adequate P concentrations for increasing yields and overcoming low pH conditions. This work along with previous work evaluating efficient fertilizer management suggest the correction of a nutrient deficient soil to be more important than the source of the nutrients and supports the need for soil testing and following recommendations.

This blog is a summation of Mr. Jonathon Williams thesis which was published in the Journal of Agricultural Sciences. Impact of in-furrow fertilizer on winter wheat grain yield and mineral concentration https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021859622000557

SIDEBAR

So we do small plot research to me in control of as many variables as possible. But all farmers and consultants know that fields are are variable and the results of small plots do not always translate well. I get that 100%, but for me as a scientist I need to understand the little things so that I can apply the knowledge on a large scale. Just last month I wrote a blog about cutting phosphorus rates BLOG. The third major take home of the blog was:

A composite soil sample is an AVERAGE of the field. If your average is right at the ok level (pH of 5.6ish and M3P of 30 ppm), then half of your field is below optimum and will benefit from P.“

That applies to what we learned from the above study. We found if soil test said nutrient was adequate we did not see a response of adding more. However if we combine the two blogs, if your composite soil test comes back just at the optimum level, there is a good chance at least 45% of field is below optimum and may respond.

So guess what my recommendation is. Soil SAMPLE, do it right (proper method and core numbers) and do it at the highest resolution you can afford, at least once.

Finally Do Not Skip on Nutrients when soil test says there is a need.

BA

Any questions or comments feel free to contact me. b.arnall@okstate.edu

Phosphorus decisions, Is it worth cutting P?

With the current conditions and input cost many wheat producers are considering cutting back on inputs. I can’t disagree with the plan, but I would caution against what you cut. If you have read any of my past blogs, or seen me speak, you should know I’m all for cutting back on pre-plant nitrogen (N). Based on some recent trials I would not argue cutting the potassium (K) side, but phosphorus (P) that’s another story that we will walk through in this blog.

First and foremost, soil testing is the key to P management. If your soil test is below the critical threshold for the test you use, 32.5 for Mehlich 3 (M3P), then you need to add phos. We have enough work that shows current recommendations work for P in wheat. Reeds paper Evaluation of incorporated phosphorus fertilizer recommendations on no-till managed winter wheat Link to Paper goes over soil test recommendations in no-till and the recent double crop soybean project Double Crop P and K Blog highlights the importance of P fertility, regardless of yield level. Also if your soil test is below a 5.5 and you haven’t limed (Liming is the best solution, Band-aids not so cheap Blog ), then the next best option is adding additional P to alleviate the aluminum toxicity Band-aids for low pH Blog. In-short if the fields soil test P and or pH is below optimum you should not forgo P application.

But the primary reason I am writing this blog is for those looking at fields with composite soil test that is right around the critical thresholds, and they are trying to make the call on to apply P or not to apply P. Even on fields with soil test values in the good level, I am usually in favor of banding in-furrow fertilizer wheat, but not because of the same reasons I am for corn. With corn you are planting in cool soils and the availability of nutrients like P is lower in cool wet soils. For wheat cold soil isn’t the concern until we reach the end of the planting window. It will serve as a bit of a “pop-up” as the crop comes out of dormancy in the spring. I have also seen little to no value of N applied in furrow. I see same response to DAP (18-46-0), MAP (11-52-0), and TSP (0-46-0) when all applied at same rate of P. Meaning it was the P not N making the difference.

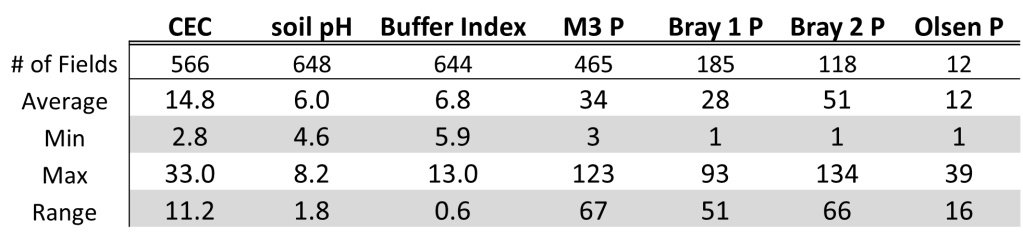

For me the reason I still recommend getting a little phosphate out even when the soil test comes back is that the great majority of fields have a large range of variability. Looking at a set of 650 grid sampled fields across Oklahoma and Kansas it showed on average soil pH 6.0 and M3P was 34 ppm. Both pH and P are at adequate/optimum levels. However, the average is usually somewhere between the low and high point and in this data set and the range of soil pH was 1.8 units and the range in M3P was 67 ppm. That meant on average of the 648 field with pH values the average difference between low pH and high pH was 1.8 units and the difference between low P and high P was 64 ppm.

The field below is from Kingfisher county and was sampled at a resolution of 10 acres per sample. This is a fairly course resolution for grid sampling but provides a great view of how variable our soils can be. The field average pH is 5.3, which is below optimum but our aluminum tolerant wheats would be able to handle fairly well. For the P the average is 22 ppm which needs about 18 lbs of P2O5 to max yields. If the farmer applied a flat rate of 20 lbs there would be significant forage loss on about 65% of the field, for grain only about 45% of the field due to underapplication of P. Note that low P and low pH are not correlated well, meaning the areas low in pH are not always low in P.

Banding P makes it more efficient because it slows the rate of tie. However, we have plenty data that says broadcast applied P is still a great option, even after planting. So what are my take homes from this blog?

First: If you are grazing wheat get down 40-50 lbs of N pre. But I have plenty of data the pre-plant N on grain only wheat is not needed. I have the same amount of data that shows the only value of in-furrow N for grain only is that it forces you to plant more seeds, because it just lowers stand.

Second: When it comes to wheat pay attention to Phosphorus and soil pH. Even our acid tolerant wheats preform better in neutral soil pHs, especially forage wise.

Third: A composite soil sample is an AVERAGE of the field. If your average is right at the ok level (pH of 5.6ish and M3P of 30 ppm), then half of your field is below optimum and will benefit from P.

Fourth: If you can band P great, but if you cant broadcast is still a viable option. Do Not Skip P when soil test says there is a need.

Questions or comments please feel free to reach out.

Brian Arnall b.arnall@okstate.edu

Top-dress Wheat with P and K ??

Brian Arnall, Precision Nutrient Management Extension Specialist

Hunter Lovewell, Past PNM MS student.

Original Blog Name: Managing P and K in a wheat Double-crop Soybean System.

I planned to wait until the soybean yields came in to share the data from this project, but the wheat results are just too interesting this year.

So the trial posed the question, when is the best time to apply the phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) for the soybean crop in a wheat double crop soybean system, if any is needed above what is applied for the wheat crop. We applied the wheat’s P&K at establishment, but the soybeans P&K was applied either at wheat establishment, top-dress wheat timing, or post wheat harvest pre soybean planting. We used the sources of granular triple super phosphate (0-46-0) and potash (0-0-60) for all applications. We hypothesized the wheat crop would not benefit from the soybeans portion of P&K and that the top-dress application timing for the soybeans P&K would result in the greatest soybean yields.

So far, we have six site years with completed cycles with locations at the Eastern Research Station (ERS) near Haskell, Oklahoma, Ballagh Family Research Farm (BF) near Newkirk, Oklahoma, Skagg Family Farm (SF) near Lamont, Oklahoma, and Lake Carl Blackwell Research Farm (LCB) near Perry, Oklahoma. The research was conducted during the 2019-2020 growing season and the 2020-2021 growing season. For the 2021-2022 cycle we added two more locations one again on the Skagg Family farm and the second on a new cooperator, O’Neil Farms (OF) near Ponca City. For all locations no P or K was applied by the farmers at any point, but they did manage IPM. See location descriptions below.

The first two years of work is written up in Mr. Hunter Lovewell’s thesis titled “EFFECTS OF PHOSPHOROUS AND POTASSIUM APPLICATION TIMING ON A WHEAT DOUBLE-CROP SOYBEAN SYSTEM” which I can share with those interested. To be honest, Hunter had a couple tough seasons. Basically where wheat did well, beans typically failed and where you had good beans the previous wheat had failed. All the same he had some interesting results. What follows is pulled from his conclusions.

“While a significant response to the application of P and K was limited, the results show that there are environments in which the wheat crop can benefit from additional P and K fertilizer applied for the soybean crop. In the case of the soil (SF-SH) with low M3P and an acidic soil pH, the additional P applied during the winter wheat growing season, intended for soybeans, alleviated the aluminum toxicity issues with acidic pH, increasing wheat yields. Beyond the single location with low soil test P and pH no other significant response was found to the addition of and P. This may be explained in that most locations were only marginally deficient P and the majority of the varieties used in the study were considered to have acid soil tolerance. Penn and Arnall (2015) found that cultivars with aluminum tolerance had increased P use efficiency. The BF location showed a significant wheat grain yield response to the K fertilization, but the additional K applied for the soybean crop showed no benefit for the wheat crop. While there was no significant increase in soybean grain yield to the additional K fertilizer observations suggest that the application of K fertilizer for soybeans may be of benefit. As was mentioned before the double-crop system is susceptible to yield-limiting conditions, heat, and moisture, due to the maturity of the crop during the peak summer months. The soybean grain yields achieved in this study were all below the previous five-year yield average for all the locations. The low achieved yields and crop stress may have limited this study’s ability to identify a significant response to the application of fertilizer. “

So, one of the most interesting finding from the first six sites was that topdressing P increased yield of the wheat crop on the soil that had low pH and P. And since the P recs applied were only considering STP values and not soil pH, we had underapplied P for the wheat.

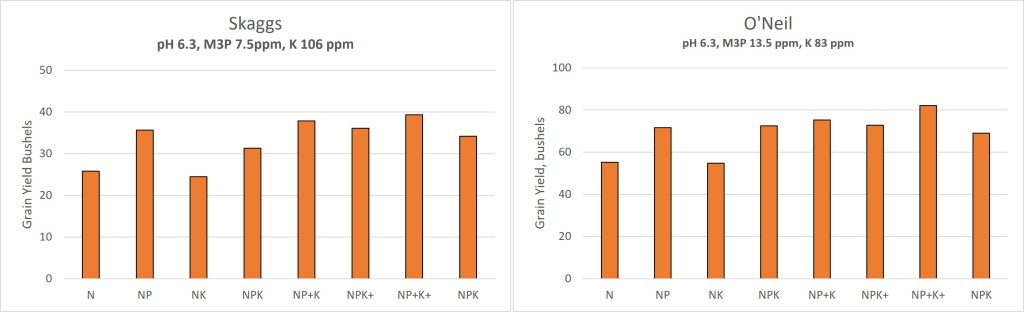

Now moving on to the 2021-22 season. Well as most of the famers know, this season has been a doozy. That said, we were not able to establish the treatments until February 1st. Therefor in the case of the 2021-22 wheat season the first application of P&K was made at top-dress timing and then the second application was made post wheat harvest. So, we are unable to say how a preplant wheat P&K application would have performed. But the wheat grain yield response to P&K was better than I could have ever imagined.

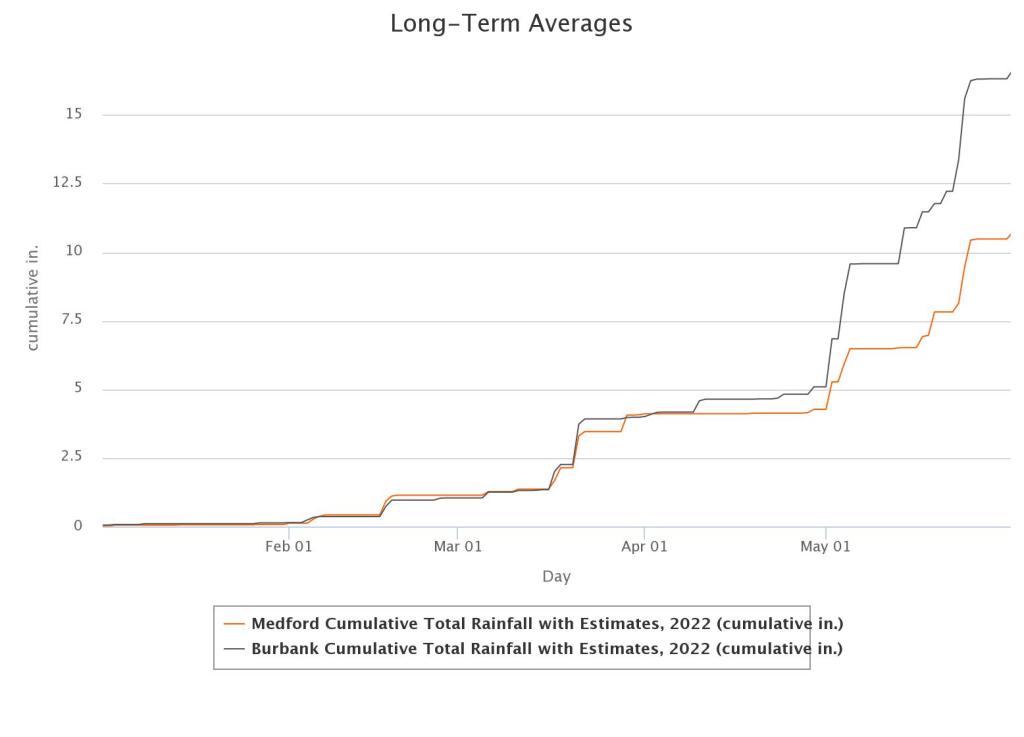

The rain post application (Feb 1st) was marginal but better than other areas in the central/southern Plains. There was about 1” of precipitation in February, almost 3” in March and under 0.2” in April. May rains for the OF site near Burbank aided in allowing the yields to climb, maxed out at 82 bushels per acre, while the SF-Nfld missed out on many of the late rains and yields topped out at 39 bushels.

At both sites there is a clear and distinct response to P fertilizer. Note the N and NK treatments significantly lower than all other treatments. The last column on each figure title NPK is the average of all other treatments that only received the wheats P&K rate and had yet had the soybeans P&K applications.

We were able to statistically analyze the locations together by calculating a relative yield for each location. This is done by dividing the yield of each plot by the yield of the N only treatment, we did this for each replication. We then ran a t-test to look at significant treatment difference, so below any treatments that has the letters above the columns, such as an ab and b, are not statistically different at a 95% level.

The relative yield data was able to confirm that across both locations an application of P in February significantly increased yields at a consistent level of 30-50%. It is interesting that while the NP+K+ treatment almost sorts out as being statistically the highest.

While I am not even close to suggesting that you should delay application of P fertilizer in wheat production, I am a big fan of in-furrow applications, this work does point to opportunities. Such as the ability to return to the field after the wheat is up and apply broadcast P if perhaps you could not at planting. But specifically, the potential for in-season Variable Rate phosphorus based upon crop response, maybe a P-Rich strip. What I can tell you this means is that I have more work to do. First, I need a better understand of when and where this is possible. Then it is time to figure out how to use this to our advantage to more efficiently use P fertilizer.

I do want to reiterate, I am not suggesting to move away from Preplant P nor in-furrow.

Keep an eye out for the soybean data because hopefully we catch a few good rains and find out if the timing of P&K will impact the double crop yields.

I want to send a big Thank you to all the cooperators who have put up with me and my time over years to get this data and the Oklahoma Soybean Board for their continued support of this project.

Feel free to send any questions for comments my way at b.arnall@okstate.edu