Home » Guest Author

Category Archives: Guest Author

Thoughts from an Agronomist- 1 Management of the Primordia

Josh Lofton, Cropping Systems Specialist

Many crop management recommendations emphasize actions that must be taken well before a crop reaches what we often call “critical growth stages.” Management this early can seem counterintuitive when the crop still looks small, healthy, or unchanged aboveground. However, much of a crop’s yield potential is determined early in the season at a level we cannot see in the field. Long before flowers, tassels, or heads (or any reproductive structure) appear, the plant is already making developmental decisions that shape its final yield potential. Understanding this “behind the scenes” process helps explain why timely, early-season management is often more effective than trying to correct problems later.

At the center of this process is the shoot apical meristem, commonly referred to as the growing point. This tissue produces leaf and reproductive primordia, which are the earliest developmental stages of future everything in the plant. These primordia form well before the corresponding plant parts are visible. Once these structures initiate—or if they fail to begin due to stress—the outcome is permanent. The plant cannot later in the season go back and recreate leaf number, leaf size, or reproductive capacity. As a result, early environmental conditions and management decisions play a disproportionate role in determining yield potential.

Corn is a good example of how early development influences final yield. By the time corn reaches the V4 growth stage, the plant only has four visible leaves with collars, yet internally it is far more advanced. Most of the total leaf primordia that will eventually form the full canopy have already begun, and the potential size of the ear is starting to be established. During this stage, the growing point is still below the soil surface and somewhat protected from some stressors but highly susceptible to others. Nitrogen deficiency, cold temperatures, moisture stress, compaction, or herbicide injury at or before V4 can reduce leaf number and limit leaf expansion. Even if growing conditions improve later, the plant cannot replace leaf primordia that were never formed, which reduces its ability to intercept sunlight and support high yields.

As corn approaches tasseling (VT), the crop enters a stage that is visually and physiologically important. Pollination, fertilization, and early kernel development occur at this time, and stress can have a critical impact on kernel set. However, by VT, the plant has already completed leaf formation, and much of the ear size potential has already been determined several growth stages earlier. Management at VT is therefore focused on protecting yield rather than creating it. Late-season nutrient applications may improve plant appearance or maintain green leaf area, but they cannot increase leaf number or rebuild ear potential lost due to early-season stress. This distinction helps explain why some late inputs show limited yield response even when the crop looks responsive.

Grain sorghum provides another clear example of why early management is emphasized. Although sorghum often grows slowly early in the season and may appear unimportant during the first few weeks after emergence, the first 30 days are among the most critical periods in its development. During this time, the growing point is actively producing leaf primordia and transitioning from vegetative growth toward reproductive development. Head size potential is primarily established during this early window, and the plant’s capacity to support tillers is influenced by early nutrient availability and moisture conditions. Stress from nitrogen deficiency, drought, weed competition, or restricted rooting during the first 30 days can reduce head size and kernel number long before visible symptoms appear.

Once sorghum reaches later vegetative and reproductive stages, much like corn at VT, management shifts from building yield potential to protecting what has already been determined. Improving conditions later in the season can help maintain plant health and grain fill, but it cannot fully compensate for early limitations imposed at the primordial level. This is why early fertility placement, timely weed control, and moisture conservation are consistently emphasized in sorghum production systems.

Across crops, a typical pattern emerges: the growth stages we observe in the field often reflect decisions the plant made weeks earlier. When agronomists stress early-season management, they are responding to plant biology rather than simply following tradition. By the time visible “critical stages” arrive, the plant has already established many of the components that define yield potential.

The key takeaway is that effective crop management must be proactive rather than reactive. Early-season decisions support the crop while it is still determining how many leaves it can produce, how large its reproductive structures can become, and how much yield it can ultimately support. Waiting until stress becomes visible often means responding after the plant has already adjusted its potential downward. Recognizing what is happening at the primordial level helps explain why management ahead of critical stages consistently delivers the greatest return, even when the crop appears small and unaffected aboveground.

For questions or comments reach out to Dr. Josh Lofton

josh.lofton@okstate.edu

Cotton disease update: Reniform nematode – 08/25/2025

Maíra Duffeck, OSU Row Crops Extension Pathologist, Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology Oklahoma State University

Maxwell Smith, OSU IPM for Cotton Extension Specialist, Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology, Oklahoma State University

Jenny Dudak, OSU Extension Cotton Specialist, Department of Plant & Soil Sciences Oklahoma State University

Reniform nematode continues to be detected in cotton fields across Oklahoma. During the 2023 and 2024 growing seasons, a survey was conducted in 17 commercial cotton fields located in Tillman, Jackson, Grady, and Caddo counties to assess the presence of parasitic nematodes affecting cotton production. We collected soil samples in areas of the fields showing irregular and stunted cotton plants.

Out of the 17 soil samples collected, reniform nematode was detected in 5 fields, marking the first confirmed report of this pest in Oklahoma cotton. Notably, in one of the positive fields, the reniform nematode population reached 1,569 nematodes per 100 cm³ of soil; more than double the economic threshold of 700 nematodes per 100 cm³. In 2025, a soil sample from a cotton field in Jackson County already tested positive for the reniform nematode.

The reniform nematode, caused by Rotylenchulus reniformis, is one of the most important yield-limiting pathogens of cotton production in the southern U.S. In addition to cotton, the reniform nematode can reproduce on other field crops such as soybean, with yield loss estimates being greater in cotton than soybean. The reniform nematode is easy to introduce into new fields because of its unique ability to survive in a dehydrated state in dry soils. Therefore, it can be transported long distances on field equipment.

We suspect that parasitic nematodes, such as root-knot and reniform nematodes, are already present in many Oklahoma cotton fields, but the damage they cause often goes unnoticed. This is especially important for the reniform nematode, as yield losses can occur without obvious aboveground symptoms. For this reason, monitoring the distribution of this nematode across the cotton fields in Oklahoma is crucial to raise awareness of this emerging issue and to guide future management decisions.

Symptoms and Signs

The expression of symptoms depends on several factors, including the susceptibility of the cotton hybrid, nematode population levels, soil type, and for how long that field has been infested. Affected plants may show reduced growth, delayed flowering, fewer fruits, and smaller fruit size, which together contribute to yield losses in lint or pods. Unlike the southern root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne incognita), the reniform nematode does not induce gall formation on roots, making field diagnosis based solely on visible symptoms challenging. For this reason, soil testing through a nematode assay is often necessary for proper identification. In newly infested fields, stunted plants are typically the most noticeable sign (Figure 1).

Plan of Action

To address this issue, a statewide nematode survey is underway to document the presence, abundance, and geographic distribution of parasitic nematodes in Oklahoma cotton fields. The information generated from this survey will provide a foundation for developing and implementing economically viable strategies to manage this issue and protect cotton production in the state.

How to participate?

Oklahoma cotton growers interested in having their fields tested for parasitic nematodes have several ways to participate in this study:

- Schedule a field visit: Contact Dr. Maira Duffeck to arrange soil sample collection. She can be reached by phone at 347-205-2180 or by email at mairodr@okstate.edu.

- Drop off samples at the Peanut & Cotton Field Day: September 18, 2025, from 5:00–8:00 p.m. at the Caddo Research Station (28054 County Street 2540, Ft. Cobb)

- Drop off samples at the Cotton Field Day: September 25, 2025, from 8:30 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. at the Southwest Research & Extension Center (16721 US Hwy 283, Altus)

More information about dropping off samples on OSU field days can be found on the flyers shown in Figures 2 and 3. Growers can submit soil samples for analysis at no cost, as expenses are covered through a project funded by the Oklahoma Cotton Council in partnership with Cotton Incorporated.

How to collect soil samples for analysis?

- Soil samples should be collected from the root zone of the plants

- Collect 15–20 soil cores (6–8 inches deep) from across the field

- Growers should focus on areas of the field where plants are showing poor growth and development

- Mix the cores thoroughly, then place the mixed soil into a resealable plastic bag

- We need about 2 pints (1 kg) of soil for analysis

- Keep samples cool — store them in a refrigerator until the field day.

- If you collect soil samples from different fields, please label and add field information to the plastic bag accordingly

For Additional Information contact.

Dr. Maíra Duffeck mairodr@okstate.edu

Toto, I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore. Double Cropping, Orange edition

It has been pointed out that the blog https://osunpk.com/2025/06/09/double-crop-options-after-wheat-ksu-edition/ had a significant Purple Haze. And I should have added the Oklahoma caveat. So Dr. Lofton has provided his take on DC corn in Oklahoma.

Double-crop Corn: An Oklahoma Perspective.

Dr. Josh Lofton, Cropping Systems Specialist.

Several weeks ago, a blog was published discussing double-crop options with a specific focus on Kansas. I wanted to address one part of that blog with a greater focus on Oklahoma, and that section would be the viability of double-crop corn as an option.

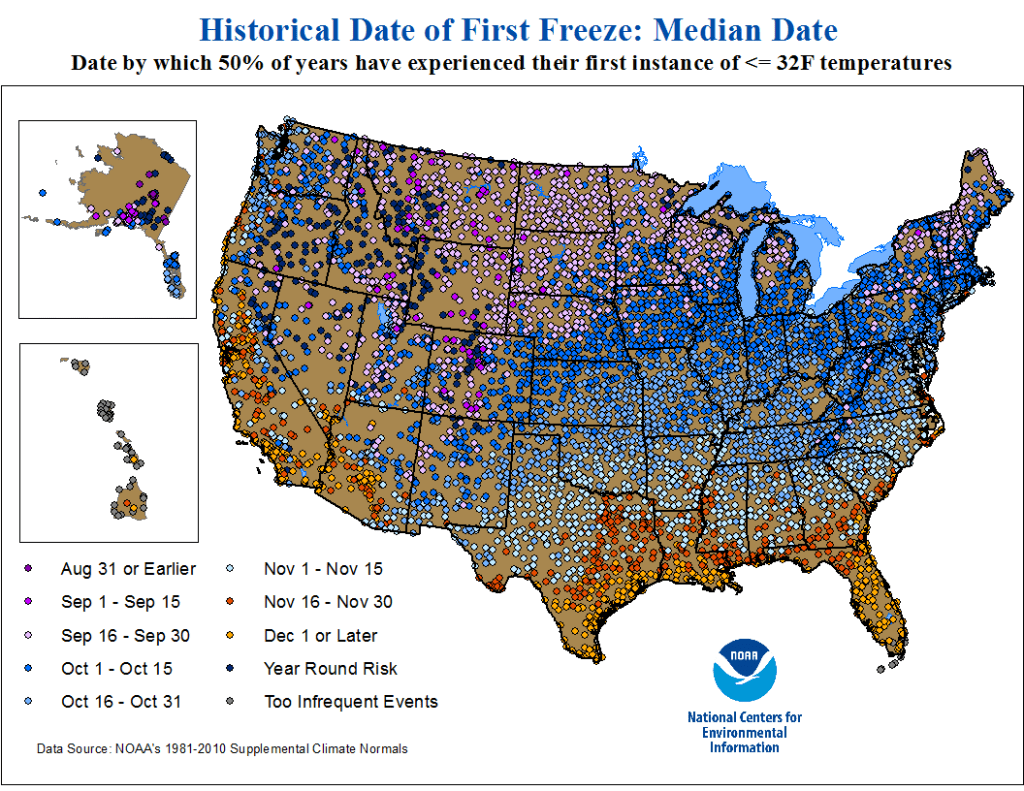

Double-crop farming is considered a high-risk, high-reward system to try. Establishing a crop during the hottest and often driest parts of summer can present challenges that need to be overcome. Double-crop corn faces these same challenges and, in some seasons, even more. However, it is definitely a system that can work in Oklahoma, especially farther south. If you look at that original blog post, one of the main challenges discussed is having enough heat units before the first frost. When examining historic data, like those below from NOAA, the first potential frost date for Northcentral and Northwest Oklahoma may be as early as the first 15 days of October but more often will be in the last 15 days of October. In Southwest and Central Oklahoma, this date shifts even later to the first 15 days of November. This is later than Kansas, especially northern Kansas, which has a much higher chance of experiencing an early October freeze. I do not want to downplay this risk; however, it is one of the biggest risks growers face with this system, and a later fall freeze would greatly benefit it. We have been conducting trials near Stillwater for the past five years on double-crop corn and have only failed the crop once due to an early freeze event. But in that year, both double-crop soybean and sorghum also did not perform well.

The main advantage of double-crop corn is that if you miss the early season window, it offers the best chance for the crop to reach pollination and early grain fill without the stress of the hottest and driest part of the year. Therefore, careful management is crucial to ensure this benefit isn’t lost. In Oklahoma, we have two systems that can support double-crop corn. In more central and southwest Oklahoma, especially under irrigation, farmers can plant corn soon after wheat harvest, similar to other double-crop systems. This planting window helps minimize the impact of Southern Rust, which can significantly reduce yields in some years, and may reduce the need for extensive management. This earlier planting window is often supported by irrigation, enabling the crop to endure the hotter, drier late July and early August periods. Conversely, in northern Oklahoma, planting often occurs in July to allow pollination and grain fill (usually 30-45 days after emergence) to happen in late August and early September. During this period, the chances of rainfall and cooler nighttime temperatures increase, both of which are critical for successful corn production.

Other management considerations include maturity. Based on initial testing in Oklahoma, particularly in the northern areas, we prefer to plant longer-maturity corn. Early corn varieties have a better chance of maturing before a potential early freeze but also carry a higher risk of undergoing critical reproduction stages (pollination and early grain fill) during hot, dry periods in late summer. Testing indicates that corn with a maturity of over 110 days often works well for this. However, this does not mean growers cannot plant shorter-season corn, especially if the season has generally been cooler, though the risk still exists depending on how quickly the crop can grow. Based on testing within the state, the dryland double-crop corn system typically does not require adjustments to other management practices, such as seeding rates or nitrogen application. Because of the need to coordinate leaf architecture and manage limited water resources, higher seeding rates are not recommended. Maintaining current nitrogen levels allows the crop to develop a full canopy.

The final question often comes as; how does it yield? This will depend greatly. Corn looks very good this year across that state, especially what was able to be planted earlier in the spring. However, in recent years, delaying even a couple of weeks beyond traditional planting windows has lowered yields enough that double-crop yields are often similar. We have often harvested between 50-120 bushels per acre in our plots around Stillwater with double-crop systems. So, the yield potential is still there.

In the end, Oklahoma growers know that double-crop is a risk regardless of the crop chosen. There are additional risks for double-crop corn, such as Southern Rust in the south and freeze dates in the north. This risk is increased by the presence of Corn Leaf Aphid and Corn Stunt last season, and it is not clear if these will be ongoing problems. Therefore, growers need to be careful not to expect too much or to invest too heavily in inputs that may not be recoverable if there is a loss. One silver lining is that if double-crop corn doesn’t succeed in any given year, growers can still use it as forage and recover at least some of their costs.

Any questions or concerns reach out to Dr. Lofton: josh.lofton@okstate.edu

Army Worms are Marching!!!!

This article by Brian Pugh (new OSU State Forage Specialist) just came across my desk today in perfect timing as yesterday I saw significant army worm feeding on the crabgrass in my lawn, and not to mention the 20+ caterpillars on my sidewalk. So while Brian is noting Eastern Ok, Id say we are at thresholds in Payne Co also. And no, we don’t need to discuss that my lawn as more crabgrass than Bermuda.

Fall Armyworms Have Arrived In Oklahoma Pastures and Hayfields

Brian C. Pugh, Forage Extension Specialist

Fall armyworms (FAW) are caterpillars that directly damage Bermudagrass and other introduced forage pastures, seedling wheat, soybean and residential lawns. There have been widespread reports of FAW buildups across East Central and Northeast Oklahoma in the first two weeks of July. Current locations exceeding thresholds for control are Pittsburg, McIntosh and Rogers counties.

Female FAW moths lay up to 1000 eggs over several nights on grasses or other plants. Within a few days, the eggs hatch and the caterpillars begin feeding. Caterpillars molt six times before becoming mature, increasing in size after each molt (instars). The first instar is the caterpillar just after it hatches. A second instar is the caterpillar after it has shed its skin for the first time. A sixth instar has shed its skin five times and will feed, bury itself in the soil, and pupate. The adult moth will emerge from the pupa in two weeks and begin the egg laying process again after a suitable host plant is found. Newly hatched larvae are white, yellow, or light green and darken as they mature. Mature FAW measure 1½ inches long with a body color that ranges from green, to brown to black.

Large variation in color is normal and shouldn’t be used alone as an identifying characteristic. They can most accurately be distinguished by the presence of a prominent inverted white “y” on their head. However, infestations need to be detected long before they become large caterpillars. Small larvae do not eat through the leaf tissue, but instead, scrape off all the green tissue and leave a clear membrane that gives the leaf a “window pane” appearance. Larger larvae however, feed voraciously and can completely consume leaf tissue.

FAW are “selective grazers” and tend to select the most palatable species of forages on any given site to lay eggs for young larvae to begin feeding. The caterpillars also tend to feed on the upper parts of the plant first which are younger and lower in fiber content. Forage stands that are lush due to fertility applications are often attacked first and should be scouted more frequently.

To scout for FAW, plants from several locations within the field or pasture need to be examined. Examine plants along the field margin as well as in the interior. Look for “window paned” leaves and count all sizes of larvae. OSU suggests a treatment threshold is two or three ½ inch-long larvae per linear foot in wheat and three or four ½ inch-long larvae per square foot in pasture. An easy-to-use scouting aid can be made for pasture by bending a wire coat hanger into a hoop and counting FAW in the hoop. The hoop covers about 2/3 of a square foot, so a threshold in pasture would be an average of two or three ½ inch-long larvae per hoop sample. An excellent indicator plant in forage stands is Broadleaf Signalgrass (seen in the foreground of the hay bale picture). Broadleaf Signalgrass tends to be preferentially selected by female moths and is one of the first species that window paned tissue is observed during the onset of an infestation.

Approximately 70% of the forage consumed during an armyworm’s lifetime occurs in the final instar before pupating into a moth. This indicates that control measures should focus on small instar caterpillars (1/2 inch or less) before forage loss increases exponentially. Additionally, small larvae are much more susceptible to insecticide control than larger caterpillars.

Remember, FAW are actively reproducing up until a good killing frost, so don’t let your guard down. If you think you have an infestation of fall armyworm please contact your local County Extension Educator. Additionally, before considering chemical control consult your Educator for insecticide recommendations labeled for forage use.

For more information or insecticide options consult:

Oklahoma State University factsheet:

CR-7193, Management of Insect Pests in Rangeland and Pasture

https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/management-of-insect-pests-in-rangeland-and-pasture.html

Double Crop Options After Wheat (KSU Edition)

Stolen from the KSU e-Update June 5th 2025.

Double cropping after wheat harvest can be a high-risk venture for grain crops. The remaining growing season is relatively short. Hot and/or dry conditions in July and August may cause problems with germination, emergence, seed set, or grain fill. Ample soil moisture this year can aid in establishing a successful crop after wheat harvest. Double-cropping forages after wheat works well even in drier regions of the state.

The most common double crop grain options are soybean, sorghum, and sunflower. Other possibilities include summer annual forages and specialized crops such as proso millet or other short-season summer crops, even corn. Cover crops are also an option for planting after wheat (see the companion eUpdate article “Cover crops grown post-wheat for forage”).

Be aware of herbicide carryover potential

One major planting consideration after wheat is the potential for herbicide carryover. Many herbicides applied to wheat are Group 2 herbicides in the sulfonylurea family with the potential to remain in the soil after harvest. If a herbicide such as chlorsulfuron (Glean, Finesse, others) or metsulfuron (Ally) has been used, then the most tolerant double crop will be sulfonylurea-resistant varieties of soybean (STS, SR, Bolt) or other crops. When choosing to use herbicide-resistant varieties, be sure to match the resistance trait with the specific herbicide (not only the herbicide group) that you used. This is especially true when looking at sunflowers as a double crop. There are sunflowers with the Clearfield trait, which allows Beyond herbicide applications, and ExpressSun sunflowers, which allow an application of Express herbicide. While both of these herbicides are Group 2 (ALS-inhibiting herbicides), the Clearfield trait and ExpressSun are not interchangeable, and plant damage can result from other Group 2 herbicides.

Less information is available regarding the herbicide carryover potential of wheat herbicides to cover crops. There is little or no mention of rotational restrictions for specific cover crops on the labels of most herbicides. However, this does not mean there are no restrictions. Generally, there will be a statement that indicates “no other crops” should be planted for a specified amount of time, or that a bioassay must be conducted prior to planting the crop.

Burndown of summer annual weeds present at planting is essential for successful double-cropping. Assuming glyphosate-resistant kochia and pigweeds are present, combinations of glyphosate with products such as saflufenacil (Sharpen) or tiafenacil (Reviton), or alternative treatments such as paraquat may be required. Dicamba or 2,4-D may also be considered if the soybean varieties with appropriate herbicide resistance traits are planted. In addition, residual herbicides for the double crop should be applied at this time.

Management, production costs, and yield outlooks for double crop options are discussed below.

Soybeans

Soybeans are likely the most commonly used crop for double cropping, especially in central and eastern Kansas (Figure 1). With glyphosate-resistant varieties, often the only production cost for planting double crop soybeans was the seed, an application of glyphosate, and the fuel and equipment costs associated with planting, spraying, and harvesting. However, the spread of herbicide-resistant weeds means additional herbicides will be required to achieve acceptable control and minimize the risk of further development of resistant weeds.

Weed control. The weed control cost cannot really be counted against the soybeans, since that cost should occur whether or not a soybean crop is present. In fact, having soybeans on the field may reduce herbicide costs compared to leaving the field fallow. Still, it is recommended to apply a pre-emergence residual herbicide before or at planting time. Later in the summer, a healthy soybean canopy may suppress weeds enough that a late-summer post-emergence application may not be needed.

Variety selection for double cropping is important. Soybeans flower in response to a combination of temperature and day length, so shifting to an earlier-maturing variety when planting late in a double crop situation will result in very short plants with pods that are close to the ground. Planting a variety with the same or perhaps even slightly later maturity rating (compared to soybeans planted at a typical planting date) will allow the plant to develop a larger canopy before flowering. Planting a variety that is too much later in maturity, however, increases the risk that the beans may not mature before frost, especially if long periods of drought slow growth. The goal is to maximize the length of the growing season of the crop, so prompt planting after wheat harvest time is critical. The earlier you can plant, the higher the yield potential of the crop if moisture is not a limiting factor.

Fertilizer considerations. Adding some nitrogen (N) to double-crop soybeans may be beneficial if the previous wheat yield was high and the soil N was depleted. A soil test before wheat harvest for N levels is recommended. Use no more than 30 lbs/acre of N. It would be ideal to knife-in the fertilizer. If that is not possible, banding it on the soil surface would be acceptable. Do not apply N in the furrow with soybean seed as severe stand loss can occur.

Seeding rates and row spacing. Seeding rate can be slightly increased if soybeans are planted too late in order to increase canopy development. Narrow row spacing (15-inch or less) has often resulted in a yield advantage compared to 30-inch rows in late plantings. Soybeans planted in narrow rows will canopy over more quickly than in wide rows, which is important when the length of the growing season is shortened. Narrow rows also offer the benefits of increasing early-season light capture, suppressing weeds, and reducing erosion. On the other hand, the advantage of planting in wide rows is that the bottom pods will usually be slightly higher off the soil surface to aid harvest. The other consideration is planting equipment. Often, no-till planters will handle wheat residue better and place seeds more precisely than drills, although the difference has narrowed in recent years.

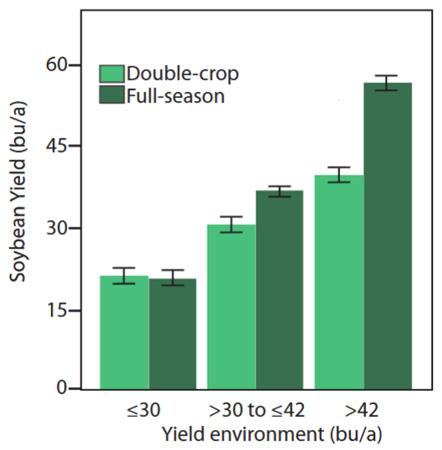

What are typical yield expectations for double-crop soybeans? It varies considerably depending on moisture and temperature, but yields are usually several bushels less than full-season soybeans. A long-term average of 20 bushels per acre is often mentioned when discussing double-crop soybeans in central and northeast Kansas. Rainfall amount and distribution can cause a wide variation in yields from year to year. Double-crop soybean yields typically are much better as you move farther southeast in Kansas, often ranging from 20 to 40 bushels per acre.

A recent publication explores the potential yield of double-crop soybeans relative to full-season yield (Figure 2) and the most limiting factors affecting the yields for double-crop soybeans. The link to this article is: https://bookstore.ksre.ksu.edu/pubs/MF3461.pdf.

Grain Sorghum

Grain sorghum is another double crop option. Unlike soybeans, sorghum hybrids for double cropping should be earlier maturing hybrids. Sorghum development is primarily driven by the accumulation of heat units, and the double crop growing season is too short to allow medium-late or late hybrids to mature before the first frost in most of Kansas.

Seeding rates and row spacing. Late-planted sorghum likely will not tiller as much as early plantings and can benefit from slightly higher seeding rates than would be used for sorghum planted at an earlier date. Narrow row spacing is advised, especially if the outlook for rainfall is good.

Fertilizer considerations. A key component for the estimation of N application rates is the yield potential. This will largely determine the N needs. It is also important to consider potential residual N from the wheat crop. This can be particularly important when wheat yields are lower than expected. In that situation, additional available N may be present in the soil. Assess the amount of profile N by taking soil samples at a depth of 24 inches and submitting them for analysis at a soil testing laboratory.

Double crop sorghum planted into average or greater-than-average amounts of wheat residue can result in a challenging amount of residue to deal with when planting next year’s crop. Nitrogen fertilizer can be tied up by wheat residue, so use application methods to minimize tie-up, such as knifing into the soil below the residue.

Weed control. Weed control can be important in double-crop sorghum. Warm-season annual grasses, such as crabgrass, can reduce double-crop sorghum yields. Using a chloroacetamide-and-atrazine pre-emergence product may be key to successful double-crop sorghum production. Herbicide-resistant grain sorghum varieties will allow the use of imazamox (Imiflex in igrowth sorghums) or quizalofop (FirstAct in DoubleTeam grain sorghum) that can control summer annual grasses.

No-till studies at Hesston documented 4-year average double crop sorghum yields of 75 bushels per acre compared to about 90 bushels per acre for full-season sorghum. A different 10-year study that did not have double crop planting but did compare early- and late-planting dates averaged 73 bushels per acre for May planting vs. 68 bushels per acre for June planting.

Sunflowers

Sunflowers can be a successful double crop option anywhere in the state, provided there is enough moisture at planting time to get a stand. Sunflowers need more moisture than any other crop to germinate and emerge because of the large seed. Therefore, stand establishment is important. Planting immediately after wheat harvest on a limited irrigation field can be a good fit to help with stand establishment.

Seeding rates and hybrid selection. When double-cropping sunflowers, producers should use similar seeding rates to what is typical for the area for full-season sunflowers. While full-season sunflowers can be successful in double-crop production, utilizing shorter-season hybrids can increase the likelihood of the sunflowers blooming and maturing before a killing frost.

Weed control. First, it is important to check the herbicide applications on the wheat. The rotation restriction to sunflowers after several commonly used wheat herbicides is 22-24 months.

Weed control can be an issue with double-crop sunflowers since herbicide options are limited, especially post-emergence. Thus, controlling weeds prior to sunflower planting is critical and may be complicated pre-plant restrictions for some herbicides. Planting Clearfield or ExpressSun sunflowers will provide additional post-emergence herbicide options, but ALS-resistant kochia and pigweeds still won’t be controlled. Imazamox (Beyond in Clearfield sunflower) has activity on small annual grasses as well as many broadleaf weeds, if they are not ALS-resistant.

Summer annual forages

With mid-July plantings, and where herbicide carryover issues are not a concern, summer annual sorghum-type forages are also a good double crop option. A study planted July 21, 2008 near Holton, when summer rainfall was very favorable, provided yields of 2.5 to 3 tons dry matter/acre for hybrid pearl millet and sudangrass at the low end to 4 to 5 tons dry matter/acre for forage sorghum, BMR forage sorghum, photoperiod sensitive forage sorghum, and sorghum x sudangrass hybrids. Earlier plantings may produce even more tonnage, as long as there is adequate August rainfall.

One challenge with late-planted summer annual forages is getting them to dry down when harvest is delayed until mid- to late-September. Wrapping bales or bagging to make silage are good ways to deal with the higher moisture forage this late in the year.

Corn

Is double-crop corn a viable option? Corn is typically not recommended for late June or July plantings because yield is usually substantially less than when planted earlier.

Typically, mid-July planted corn struggles during pollination and seldom receives sufficient heat units to fill grain before frost. Very short-season corn hybrids (80 to 95 RM) have the greatest chance of maturing before frost in double crop plantings, but generally have less yield potential when compared to hybrids of 100 RM or more used for full-season plantings. Short-season hybrids often set the ear fairly close to the ground, increasing the harvest difficulty. Glyphosate-resistant hybrids will make weed control easier with double crop corn, but problems remain present with late-emerging summer weeds such as pigweeds, velvetleaf, and large crabgrass. Keep in mind, corn is very susceptible to carryover of most residual ALS herbicides used in wheat.

Considerations for altering seeding rates and variety/hybrid maturity for the crops discussed above are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Seeding rate and variety/hybrid relative maturity considerations for double crops compared to full-season.

| Crop | Seeding rate | Relative maturity |

| ???????? Difference between double crop and full-season ???????? | ||

| Soybean | Increase | No change or longer |

| Sorghum | Increase | Shorter |

| Sunflower | No change | Shorter |

| Corn | No change | Shorter |

Volunteer wheat control

One of the issues with double cropping that is often overlooked by producers is the potential for volunteer wheat in the crop following wheat. If volunteer wheat emerges and goes uncontrolled, it can cause serious problems for nearby wheat fields in the fall as a host for the wheat streak mosaic complex of viruses [wheat streak mosaic (WSMV), High Plains disease (HPD), and triticum mosaic (TriMV)] that are transmitted by the wheat curl mite (WCM).

Volunteer wheat can generally be controlled fairly well with glyphosate or Group 1 herbicides such as quizalofop (Assure II, others), clethodim (Select Max, others), or sethodydim (Poast Plus, others), but control is reduced during times of drought stress. Atrazine can provide control of volunteer wheat in double-crop corn or sorghum, but control can be erratic depending on rainfall patterns.

For more detailed information about herbicides, see the “2025 Chemical Weed Control for Field Crops, Pastures, and Noncropland” guide available online at https://www.bookstore.ksre.ksu.edu/pubs/CHEMWEEDGUIDE.pdf or check with your local K-State Research and Extension office for a paper copy. The use of trade names is for clarity to readers and does not imply endorsement of a particular product, nor does exclusion imply non-approval. Always consult the herbicide label for the most current use requirements.

To Subscribe to the KSU Agronomy E-Updates follow this link

https://eupdate.agronomy.ksu.edu/index_new_prep.php

Authors contributing to the post

Sarah Lancaster, Weed Management Specialist

slancaster@ksu.edu

John Holman, Cropping Systems Agronomist

jholman@ksu.edu

Logan Simon, Southwest Area Agronomist

lsimon@ksu.edu

Tina Sullivan, Northeast Area Agronomist

tsullivan@ksu.edu

Jeanne Falk Jones, Multi-County Agronomist

jfalkjones@ksu.edu

Meet the Aster Leafhopper and Learn How to Distinguish it from the Corn Leafhopper

Ashleigh M. Faris: Extension Cropping Systems Entomologist, IPM Coordinator

Release Date June 3 2025

Last year’s corn stunt disease outbreak, caused by the corn leafhopper transmitting pathogens associated with corn stunt disease, has been on everyone’s minds. Over the past few weeks, I’ve received several calls from growers, crop consultants, and industry partners concerned about leafhoppers in corn. Fortunately, none have been corn leafhoppers, the vast majority have instead been aster leafhoppers. So far, no corn leafhoppers have been reported north of central Texas. Oklahoma did not have any reports of overwintering corn leafhoppers so if we have the insect this year it will need to migrate northward from where it currently resides. For a refresher on the corn leafhopper and corn stunt disease, check out these two previously posted OSU Pest e-Alerts: EPP-25-3and EPP-23-17.

Leafhoppers in general are insects that we have had for many years in our row and field crops. But we likely did not pay attention to them or notice them until this past year due to our heightened awareness of their existence thanks to the corn leafhopper and corn stunt disease. Below is guidance on how to distinguish between the corn leafhopper and aster leafhopper. Remember, if the corn leafhopper is detected in the state, OSU Extension will notify growers, consultants, and industry partners through Pest e-Alerts and our social media channels.

Aster Leafhopper Overview

The aster leafhopper (aka six spotted leafhopper), Macrosteles quadrilineatus, is native to North America and can be found in every U.S. state, as well as Canada. This polyphagous insect feeds on over 300 host plant species including weeds, vegetables, and cereals. Like many other leafhoppers, the aster leafhopper can be a vector of pathogens that cause disease, but corn stunt is not one of them. Instead, aster leafhoppers cause problems in traditional vegetable growing operations, as well as floral production. There is currently no concern for this insect being a vector of disease in row or field crops, including corn. Check out the OSU Pest a-Alert EPP-23-1to learn more about this insect and aster yellows disease.

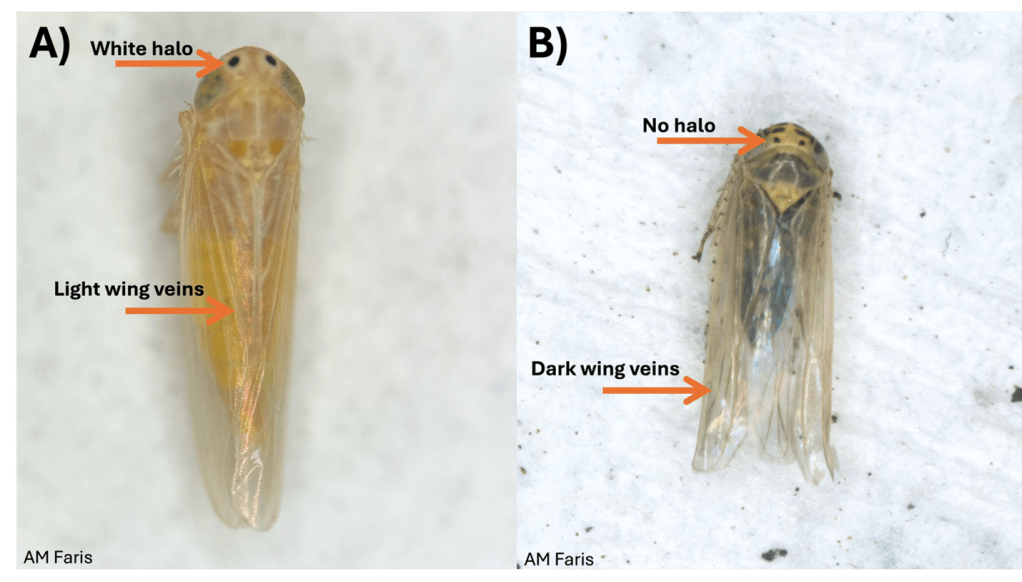

Aster Leafhopper versus Corn Leafhopper

The corn leafhopper (Photo 1A) and the aster leafhopper, as well as many other leafhopper species have two black dots located between the eyes of the insect (Photo 1). Aster leafhopper adults are 0.125 inches (3 mm) long, with transparent wings that bear strong veins, and darkly colored abdomens (Photo 1B). Their dark abdomen can cause the aster leafhopper to appear grey when you see them in the field. Their long wings can also make the insect appear to have a similar appearance to the corn leafhopper (Dalbulus maidis) (Photo 1).

Characteristics that differentiate the corn leafhopper from the aster leafhopper are as follows. When viewed from above (dorsally): 1) the corn leafhopper’s dots between the eyes have a white halo around them and the aster leafhopper’s dots between eyes lack the white halo and 2) the corn leafhopper has lighter/finer wing veination than the aster leafhopper (Photo 1). When when viewed from their underside (ventrally) 3) the corn leafhopper lacks markings on their face whereas the aster leafhopper has lines/spot on the face and 4) the abdomen of the corn leafhopper lacks the dark coloration of the aster leafhopper (Photo 2).

Confirming Corn Leafhopper Identification

It is important to note that many insects will have their cuticle darken as they age. This, along with there being light and dark morphs of many insects can lend to additional confusion when distinguishing one species from another. If you believe that you have a corn leafhopper then you need to collect the insect and send it to a trained entomologist that can verify the identity of the insect under the microscope. Leafhoppers in general are fast moving insects but they can be collected in an insect net or using a handheld vacuum (see EPP-25-3). You can submit samples to the OSU Plant Disease and Insect Diagnostic Lab.

Please feel free to reach out to OSU Cropping Systems Extension Entomologist Dr. Ashleigh Faris with any questions or concerns. @ ashleigh.faris@okstate.edu

PRE-EMERGENT RESIDUAL HERBICIDE ACTIVITY ON SOYBEANS, 2025

Liberty Galvin, Weed Science Specialist

Karina Beneton, Weed Science Graduate Student.

Objective

Determine the duration of residual weed control in soybean systems following the application of Preemergent (PRE) herbicides when applied alone and in tank-mix combination.

Why we are doing the research

PRE herbicides offer an effective means of suppressing early-season weed emergence, thereby minimizing competition during the critical early growth stage. However, evolving herbicide resistance and the need for longer-lasting weed suppression underscore the importance of evaluating multiple modes of action and their residual properties alone and tank-mixed.

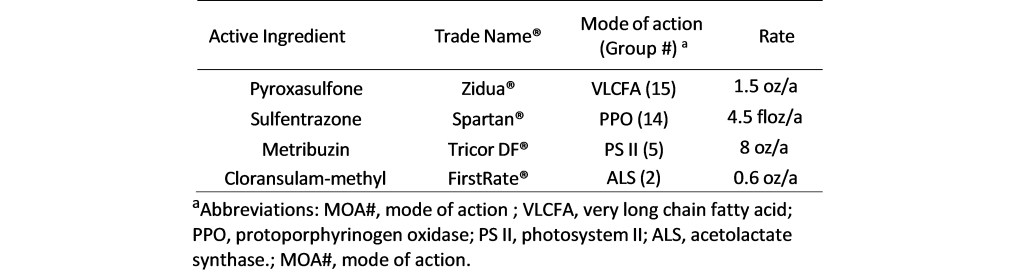

Field application experimental design and methods

Field experiments were conducted in 2022, 2023, and 2024 growing seasons in Bixby, Lane, and Ft. Cobb FRSU Research Stations across Oklahoma. Each herbicide (listed in Table 1) was tested individually, in 2-way combinations, 3-way mixtures, and finally as 4-way combinations that included all active ingredients listed at the label rate.

Soybeans were planted at rates between 116,000 and 139,000 seeds/acre from late May to early June, depending on the year and location. The variety used belongs to the indeterminate mid- maturity group IV, with traits conferring tolerance to glyphosate (group 9 mode of action), glufosinate (group 10), and dicamba (group 4). Not all soybean varieties have metribuzin tolerance. Please read the herbicide label and consult your seed dealer for acquiring tolerant varieties. Row spacing was 76 cm at Bixby and Lane, and 91 cm at Fort Cobb. PRE treatments were applied immediately after planting at each experimental location.

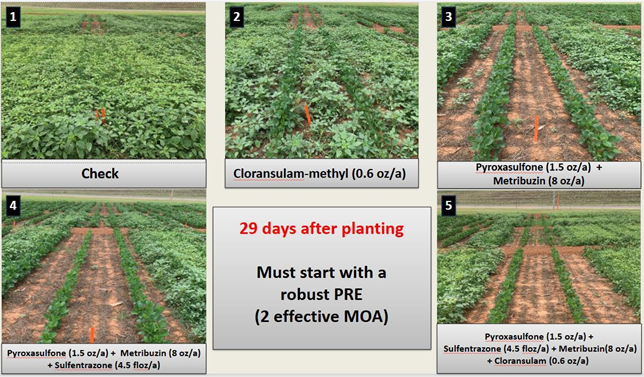

POST applications consisted of a tank-mix of dicamba (XtendiMax VG® – 22 floz/acre), glyphosate (Roundup PowerMax 3®- 30 floz/acre), S-metolachlor (Dual II Magnum® – 16 floz/acre), and potassium carbonate (Sentris® – 18 floz/acre). Applications were made on different dates, mostly after the first 3 weeks following PRE treatments. These timings were based on visual weed control ratings, particularly for herbicides applied alone or in 2-way combinations, which showed less than 80% control at those early evaluation dates. The need for POST applications also depended on the species present at each site, with most fields being dominated by pigweed, as illustrated in the figure below.

Results

Tank-mixed PRE herbicide combinations generally provided superior residual control compared to a single mode of action application (Shown in Figure 1). Timely post-emergent (POST) herbicide applications helped sustain high levels of weed suppression, particularly as the effectiveness of residual PRE declined.

Residual control of tank-mixed PRE

Some herbicides applied alone or in simple 2-way mixes, such as sulfentrazone + chloransulam- methyl and pyroxasulfone + chloransulam-methyl required POST applications within 20 to 29 days after PRE, indicating moderate residual control.

In contrast, 2-way combinations containing metribuzin, such as sulfentrazone + metribuzin and pyroxasulfone + metribuzin, extended control up to 50 days after PRE in some cases, highlighting metribuzin’s importance even in less complex formulations.

Furthermore, 3-way and 4-way combinations including metribuzin provided the longest-lasting control, delaying POST applications up to 51–55 days after PRE.

Injury of specific weeds

Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) control in Bixby was consistently high (≥90%) at 2 weeks after PRE in 2022 and 2024 across all treatments. At 4 WAPRE, treatments containing metribuzin alone or in combination maintained strong control (90% or greater).

Texas millet (i.e., panicum; Urochloa texana) and large crabgrass (Digitaria sanguinalis) were effectively managed with most treatments delivering over 90% control early in the season and maintaining performance throughout. In 2024, control remained generally effective, though pyroxasulfone alone showed a temporary lack of control for Texas millet, and single applications declined in effectiveness against large crabgrass later in the season. These reductions were likely due to continuous emergence and the natural decline in residual herbicide activity due to weather. The most consistent late-season control for both species came from 3- and 4-way herbicide combinations.

Morningglory (Ipomoea purpurea) control reached full effectiveness (100%) only when POST herbicides were applied, across all years and locations. Their late emergence beyond the residual window of PRE herbicides reinforces the importance of sequential herbicide applications for season-long control.

Take home messages:

- Incorporating PRE and POST herbicides slows the rate of herbicide resistance

- Tank mixing with *different modes of action* ensures greater weed control by having activity on multiple metabolic pathways within the plant.

- Tank mixing with PRE herbicides could reduce the number of POST applications required, and

- Provides POST application flexibility due to residual of PRE application

For additional information, please contact Liberty Galvin at 405-334-7676 | LBGALVIN@OKSTATE.EDU or your Area Agronomist extension specialist.

Management of soybean inoculum

Josh Lofton, Cropping Systems Specialist

Brian Arnall, Precision Nutrient Management Specialist

Soybean, a legume, can form a symbiotic relationship with Bradyrhizobium japonicum (Kirchner, Buchanan) and create their N to supplement crop demands. However, this relationship depends upon these beneficial microorganisms’ presence and persistence in the soil. This specific strain of microorganisms is not native to Oklahoma and thus must be supplemented using inoculum as a seed treatment. However, the use of inoculums alone does not guarantee a successful relationship. Handling, storage, soil conditions, and other factors can impact the ability of these microorganisms to do their job.

Soybean nitrogen demand is high, with most reports indicating that soybeans need 4.5 to 5.0 pounds of nitrogen per bushel of grain yield. This means that a 30-bushel crop requires between 135 and 150 pounds of nitrogen per acre (in comparison, corn and wheat need only 0.8 or1.6 pounds, respectively). This relationship has been shown to supply an equivalent of 89 lbs of N to the soil. In the previous example, these bacteria could fulfill 50-90% of nitrogen demand, reducing input costs significantly.

However, the bacteria associated with soybean inoculum are living organisms. Therefore, the conditions they experience before being applied to the seed and after treatment (including both before and following planting) can significantly impact their relationship with the soybean plant and, thus, their ability to provide N to the plant. By introducing a high concentration of bacteria near the seed and emerging root, this symbiotic relationship is more likely to be established quickly.

The importance of using inoculum is often debated in Oklahoma, particularly given the fluctuating prices of commodities and inputs. A recent assessment of various soybean-producing areas throughout the state revealed that most fields experienced advantages from incorporating soybean inoculation (Figure 1).

These benefits can be seen when the inoculum maintains viability until it is planted. It is always recommended that the bacteria be stored in a cool, dark environment before application on the seed. These conditions help preserve the survival of these bacteria outside of the host relationship. An evaluation of soybean inoculant after being stored short-term in different conditions found that in as little as 14 days, viability can decrease when kept in non-climate-controlled conditions (Figure 2). Additionally, viability was further reduced at 21 days when stored at room temperature compared to a refrigerated system

However, conditions colder than this, such as the use of a freezer, can compromise survival as well. Storing inoculum in the freezer forms ice crystals within the living cells and damages the cell membranes, making the microorganisms less likely to be alive upon rethawing. Additional chemicals can be added to increase the viability of long-term storage and sub-freezing temperatures. From an application standpoint, a new product should be purchased if additional storage is needed beyond short-term storage.

An additional question frequently arises: “How often should I inoculate my soybean?” As mentioned, these bacteria are not native to Oklahoma. As a result, they are not well adapted to survive in our environment and must outcompete native populations in the soil. Additionally, periods of hot and dry conditions appear to reduce the bacteria’s ability to survive without a host, the soybean roots. These are conditions we often observe in Oklahoma systems. Therefore, inoculation should be applied with every soybean planting to ensure a sufficient population of these bacteria. These bacteria promote root nodulation and nitrogen fixation in the soil.

Other soil conditions, such as excessively dry or wet soils, high or low pH, and residual nutrients, can also impact the persistence of these microorganisms. Of these, soil pH has the biggest impact on the survival of these bacteria. High pH is less of a concern to Oklahoma production systems; however, soil with lower pH should be remediated. Like many bacterial systems, these bacteria optimally function at a pH range that closely resembles the ideal pH range for most crops. Lowering the soil pH below a critical threshold reduces the viability of the bacteria, hampers N-fixation processes, and diminishes the capacity of both the bacteria and soybean plants to form and maintain this relationship. While applying inoculum to soybean seeds in these adverse soil conditions can provide some advantages (Figure 3), but it often doesn’t increase yields. Therefore, inoculation with corresponding adjustments to soil pH represents the best approach.

While using inoculum is not a new concept, it is important to highlight the benefits it can provide when utilized correctly. The potential to reduce N input costs is attractive, but the effectiveness depends on proper handling, storage, and soil conditions until it can intercept the host. To maximize benefits, inoculum should be stored in a cool, dark environment and utilized in a timely manner. If there is doubt that there are not enough bacteria, an inoculum should be added. Oklahoma’s climate, particularly hot and dry conditions, can limit bacteria survival, reinforcing the need to treat the inoculum until it is in the ground carefully. Additionally, considering the soil environment is important to sustain the population of bacteria until it can inoculate its host. Emphasis on these small details can have a large impact on the plant’s ability to fix nitrogen and optimize productivity throughout the growing season.

TAKE HOMES

* Soybean requires more lbs of N per bushel than most grain crops.

* Soybeans symbiotic relationship with rhizobia can provide the majority of this nitrogen.

* Soybean rhizobia is not native to Oklahoma soils so should be added to first year soybean fields.

* Inoculum should be treated with care to insure proper nodulation.

* Due to Oklahoma’s climate and existing soil conditions rhizobia may not persist from year to year.

Any questions or comments feel free to contact Dr. Lofton or myself

josh.lofton@okstate.edu

b.arnall@okstate.edu

Appreciation of the Oklahoma Soybean Board for their support of this project.

In-Furrow Placement of Urea Products with Wheat Seed

Its that time of year I always get the question of “How much urea can I put in the furrow?”. My answer is always two fold first, I wouldn’t recommend it, its a risky venture. Even though I know some do it. Second, my research shows very little is any value from N in furrow. I like P but N just doesn’t show me any return. So for me the process is high risk, with little or no potential for return. But with blog I turn to our purple friend up north to share what their research has sown.

Brian

Guest Authors Kansas State University

Lucas Haag, Agronomist-in-Charge, Southwest Research-Extension Center, Tribune lhaag@ksu.edu

Alan Schlegel, retired

Dorivar Ruiz Diaz, Nutrient Management Specialist ruizdiaz@ksu.edu

To save time and cost, some wheat producers may be thinking about adding a little extra nitrogen (N) as urea or UAN to their phosphorus fertilizer through the drill with the seed. This would either be in addition to, or instead of, any preplant N applications.

While a minimum preplant N application of 20 to 40 lbs N per acre is often desirable, especially in no till production systems, there are risk involved when placing urea containing fertilizers in direct seed contact. Traditionally, we have suggested that no urea or UAN solution be placed in contact with the seed. With the continued adoption of air-seeders a common question we receive from producers is can urea, or enhanced urea products be placed in-furrow.

Methods of early-season nitrogen applications

If the starter fertilizer can’t be “spiked” with urea to add extra N, how can the necessary 20 to 40 pounds of N be applied? Subsurface banding (knifing) of N as either anhydrous ammonia, liquid UAN, or dry product will result in the greatest N use efficiency by the wheat crop. This is especially true for no-till wheat production.

If knifed N applications are not used, the next best application method would be surface banding (dribbling) of UAN solution in streams on 15- to 18-inch centers. Broadcasting urea, ammonium nitrate, or UAN applications are not generally as efficient as subsurface banding, but they are often the best choice due to equipment, logistics, or weed management considerations. Broadcast applications of N will have the most consistent performance if followed by light incorporation, precipitation, or irrigation.

Direct seed placement of nitrogen

When placing starter fertilizer in direct contact with wheat seed, producers should use the following guidelines:

The problem with placing urea-containing fertilizer with the seed is that urea is initially converted to ammonia and may be toxic to plant roots if the wheat seed is placed in direct contact with the fertilizer. Producers may hear of someone who has placed urea in direct seed contact and seemed to have no problems, but there are also many cases where urea-containing N fertilizers has injured the developing seedling and reduced or delayed emergence significantly. The risk of injury is greater in drier soils, at higher soil pH levels, and at higher N rates. High soil pH favors a higher concentration of ammonia as compared to ammonium as urea hydrolyzes. There is significant risk associated with placing urea-containing fertilizers in direct seed contact.

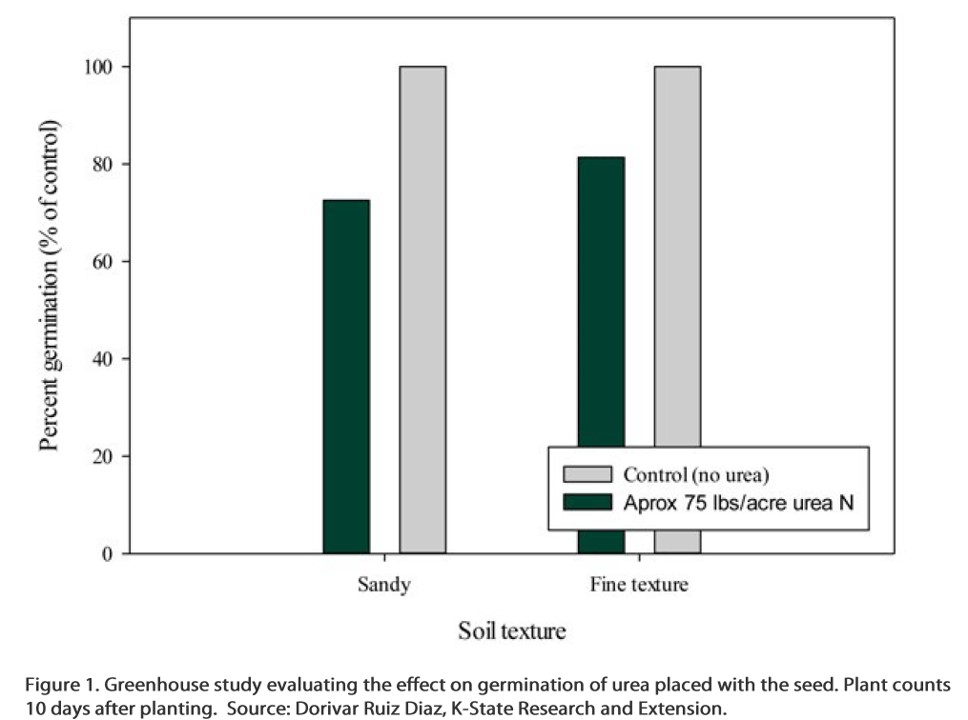

The chart below shows how soil texture affected the level of wheat germination when urea-N was applied with the seed in a K-State greenhouse study. The wheat was well watered in this study, but urea-N placed with the seed still reduced germination, especially in the sandy soil. The readings shown below were taken after 10 days. With the high rates of urea used in this study, it is possible that more damage to the seedlings would occur with time as the urea continues to hydrolyze into ammonia.

Field studies have also shown reduced wheat stands due to in-furrow placement of urea. Across 5 site years in western Kansas the placement of urea in-furrow has resulted in decreased stands at spring greenup compared to the control (Figure 2).

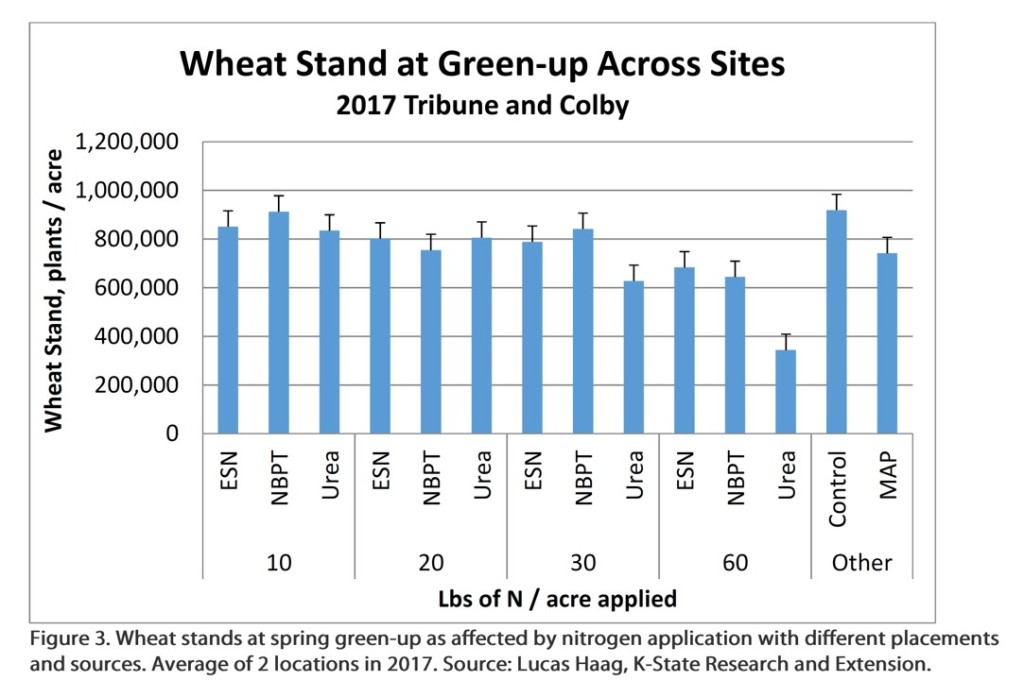

The stand reduction becomes especially noticeable at higher rate of N. One of the challenges of understanding the risk of seedling injury is that the magnitude of injury varies by field conditions an years. In some years very little reduction may be evident, even at higher rates of N, while in other years, stand reductions (and their associated impact on yield) is very evident. As an example at Tribune in 2017, reduction in stand caused by urea placement with seed, and their effect on yield were quite evident (Figures 3 and 4).

Stands were reduced 32 and 63% compared to the control when 30 and 60 lbs of N as urea were applied in-furrow (Figure 3). This resuled in yield reductions of 14 and 40%, respectively (Figure 4).

If you’d like to apply extra N directly in the seed furrow, one option is to use a controlled-release form of N, such as ESN. As shown in figure 4, at N application rates of 30 lbs/ac and less, where ESN-N was applied in-furrow, wheat yields were essentially the same as where the N was applied pre-plant, and higher compared to the same amount of N applied as urea. At the highest rate of application in the study, 60 lbs/ac, even ESN resulted in stand and grain yield reductions.

Also, air seeders that place the starter fertilizer and seed in a band an inch or two wide, or side band the fertilizer relative to the seed, provide some margin of safety because the concentration of the fertilizer and seed is lower in these diffuse bands. In this scenario, adding a little extra urea containing N fertilizers to the starter less likely to injure the seed – but it is still a risk.

Here is a great video by Dr. Haag.

Chinch bugs are active!

Both Josh Lofton and myself have been talking a lot about the magnitude of chinch bugs we’ve seen this year and the devastation they are having on the crops, both false and true chinch bugs. They have marched through sorghum and now are being found in corn fields. They seen especially bad in failed wheat fields. And in my fields anywhere I had a crabgrass. We are also hearing and seeing a significant increase in blister beetles and stink bugs in soybeans. As a soil scientist all I can recommend is to scout Often, and contact an entomologist or trusted advisor. Kansas State just put out and E-update yesterday with this article from Jeff Whitworth I wanted to share.

Chinch bugs are active in Kansas

Guest Author Jeff Whitworth, Extension Entomologist jwhitwor@ksu.edu

Chinch bugs have historically been a problem in Kansas–in lawns, golf courses, turf farms, etc. But in agriculture, they are mainly a problem in sorghum. However, they can also affect corn and occasionally wheat. Since they are true bugs, chinch bugs may attack any grass where they insert their mouthparts into the plants and suck out the juice. This often has little to no effect on the plant unless there are large numbers of bugs and/or the plants are growing under less-than-ideal conditions so that they are already stressed. Chinch bug feeding simply adds to this stress.

Sampling for chinch bugs the week of July 4 indicated that 95% of the chinch bug population in north central Kansas were adults (Figure 1). Adults don’t feed as much as nymphs but are more concerned with mating, oviposition, etc. This means the majority of feeding in crops (sorghum, corn, etc.) is still to come after the nymphs hatch (Figure 2).

Treating for chinch bugs needs to be accomplished using as much carrier (water) as practical to ensure the insecticide gets good coverage on the plants, including the base of the plants (sprays directed at the base of the plants will help). Nymphs produced now will most likely become adults in 3-4 weeks, then mate and start the process all over again for another generation, which will then move to fall-planted wheat, then on to overwintering sites. They overwinter in bunch grasses then move to wheat in the spring to deposit eggs and start all over again.

Original link https://eupdate.agronomy.ksu.edu/article_new/chinch-bugs-are-active-in-kansas-553-4

To Subscribe to KSU E-update. https://eupdate.agronomy.ksu.edu/index_new_prep.php