Home » Posts tagged 'IPM'

Tag Archives: IPM

Cotton disease update: Reniform nematode – 08/25/2025

Maíra Duffeck, OSU Row Crops Extension Pathologist, Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology Oklahoma State University

Maxwell Smith, OSU IPM for Cotton Extension Specialist, Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology, Oklahoma State University

Jenny Dudak, OSU Extension Cotton Specialist, Department of Plant & Soil Sciences Oklahoma State University

Reniform nematode continues to be detected in cotton fields across Oklahoma. During the 2023 and 2024 growing seasons, a survey was conducted in 17 commercial cotton fields located in Tillman, Jackson, Grady, and Caddo counties to assess the presence of parasitic nematodes affecting cotton production. We collected soil samples in areas of the fields showing irregular and stunted cotton plants.

Out of the 17 soil samples collected, reniform nematode was detected in 5 fields, marking the first confirmed report of this pest in Oklahoma cotton. Notably, in one of the positive fields, the reniform nematode population reached 1,569 nematodes per 100 cm³ of soil; more than double the economic threshold of 700 nematodes per 100 cm³. In 2025, a soil sample from a cotton field in Jackson County already tested positive for the reniform nematode.

The reniform nematode, caused by Rotylenchulus reniformis, is one of the most important yield-limiting pathogens of cotton production in the southern U.S. In addition to cotton, the reniform nematode can reproduce on other field crops such as soybean, with yield loss estimates being greater in cotton than soybean. The reniform nematode is easy to introduce into new fields because of its unique ability to survive in a dehydrated state in dry soils. Therefore, it can be transported long distances on field equipment.

We suspect that parasitic nematodes, such as root-knot and reniform nematodes, are already present in many Oklahoma cotton fields, but the damage they cause often goes unnoticed. This is especially important for the reniform nematode, as yield losses can occur without obvious aboveground symptoms. For this reason, monitoring the distribution of this nematode across the cotton fields in Oklahoma is crucial to raise awareness of this emerging issue and to guide future management decisions.

Symptoms and Signs

The expression of symptoms depends on several factors, including the susceptibility of the cotton hybrid, nematode population levels, soil type, and for how long that field has been infested. Affected plants may show reduced growth, delayed flowering, fewer fruits, and smaller fruit size, which together contribute to yield losses in lint or pods. Unlike the southern root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne incognita), the reniform nematode does not induce gall formation on roots, making field diagnosis based solely on visible symptoms challenging. For this reason, soil testing through a nematode assay is often necessary for proper identification. In newly infested fields, stunted plants are typically the most noticeable sign (Figure 1).

Plan of Action

To address this issue, a statewide nematode survey is underway to document the presence, abundance, and geographic distribution of parasitic nematodes in Oklahoma cotton fields. The information generated from this survey will provide a foundation for developing and implementing economically viable strategies to manage this issue and protect cotton production in the state.

How to participate?

Oklahoma cotton growers interested in having their fields tested for parasitic nematodes have several ways to participate in this study:

- Schedule a field visit: Contact Dr. Maira Duffeck to arrange soil sample collection. She can be reached by phone at 347-205-2180 or by email at mairodr@okstate.edu.

- Drop off samples at the Peanut & Cotton Field Day: September 18, 2025, from 5:00–8:00 p.m. at the Caddo Research Station (28054 County Street 2540, Ft. Cobb)

- Drop off samples at the Cotton Field Day: September 25, 2025, from 8:30 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. at the Southwest Research & Extension Center (16721 US Hwy 283, Altus)

More information about dropping off samples on OSU field days can be found on the flyers shown in Figures 2 and 3. Growers can submit soil samples for analysis at no cost, as expenses are covered through a project funded by the Oklahoma Cotton Council in partnership with Cotton Incorporated.

How to collect soil samples for analysis?

- Soil samples should be collected from the root zone of the plants

- Collect 15–20 soil cores (6–8 inches deep) from across the field

- Growers should focus on areas of the field where plants are showing poor growth and development

- Mix the cores thoroughly, then place the mixed soil into a resealable plastic bag

- We need about 2 pints (1 kg) of soil for analysis

- Keep samples cool — store them in a refrigerator until the field day.

- If you collect soil samples from different fields, please label and add field information to the plastic bag accordingly

For Additional Information contact.

Dr. Maíra Duffeck mairodr@okstate.edu

Meet the Aster Leafhopper and Learn How to Distinguish it from the Corn Leafhopper

Ashleigh M. Faris: Extension Cropping Systems Entomologist, IPM Coordinator

Release Date June 3 2025

Last year’s corn stunt disease outbreak, caused by the corn leafhopper transmitting pathogens associated with corn stunt disease, has been on everyone’s minds. Over the past few weeks, I’ve received several calls from growers, crop consultants, and industry partners concerned about leafhoppers in corn. Fortunately, none have been corn leafhoppers, the vast majority have instead been aster leafhoppers. So far, no corn leafhoppers have been reported north of central Texas. Oklahoma did not have any reports of overwintering corn leafhoppers so if we have the insect this year it will need to migrate northward from where it currently resides. For a refresher on the corn leafhopper and corn stunt disease, check out these two previously posted OSU Pest e-Alerts: EPP-25-3and EPP-23-17.

Leafhoppers in general are insects that we have had for many years in our row and field crops. But we likely did not pay attention to them or notice them until this past year due to our heightened awareness of their existence thanks to the corn leafhopper and corn stunt disease. Below is guidance on how to distinguish between the corn leafhopper and aster leafhopper. Remember, if the corn leafhopper is detected in the state, OSU Extension will notify growers, consultants, and industry partners through Pest e-Alerts and our social media channels.

Aster Leafhopper Overview

The aster leafhopper (aka six spotted leafhopper), Macrosteles quadrilineatus, is native to North America and can be found in every U.S. state, as well as Canada. This polyphagous insect feeds on over 300 host plant species including weeds, vegetables, and cereals. Like many other leafhoppers, the aster leafhopper can be a vector of pathogens that cause disease, but corn stunt is not one of them. Instead, aster leafhoppers cause problems in traditional vegetable growing operations, as well as floral production. There is currently no concern for this insect being a vector of disease in row or field crops, including corn. Check out the OSU Pest a-Alert EPP-23-1to learn more about this insect and aster yellows disease.

Aster Leafhopper versus Corn Leafhopper

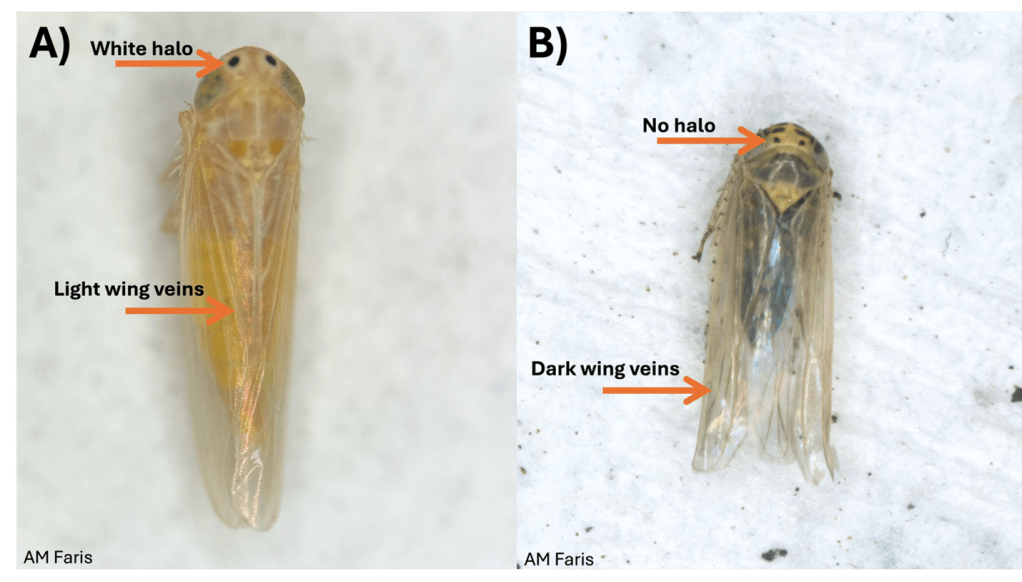

The corn leafhopper (Photo 1A) and the aster leafhopper, as well as many other leafhopper species have two black dots located between the eyes of the insect (Photo 1). Aster leafhopper adults are 0.125 inches (3 mm) long, with transparent wings that bear strong veins, and darkly colored abdomens (Photo 1B). Their dark abdomen can cause the aster leafhopper to appear grey when you see them in the field. Their long wings can also make the insect appear to have a similar appearance to the corn leafhopper (Dalbulus maidis) (Photo 1).

Characteristics that differentiate the corn leafhopper from the aster leafhopper are as follows. When viewed from above (dorsally): 1) the corn leafhopper’s dots between the eyes have a white halo around them and the aster leafhopper’s dots between eyes lack the white halo and 2) the corn leafhopper has lighter/finer wing veination than the aster leafhopper (Photo 1). When when viewed from their underside (ventrally) 3) the corn leafhopper lacks markings on their face whereas the aster leafhopper has lines/spot on the face and 4) the abdomen of the corn leafhopper lacks the dark coloration of the aster leafhopper (Photo 2).

Confirming Corn Leafhopper Identification

It is important to note that many insects will have their cuticle darken as they age. This, along with there being light and dark morphs of many insects can lend to additional confusion when distinguishing one species from another. If you believe that you have a corn leafhopper then you need to collect the insect and send it to a trained entomologist that can verify the identity of the insect under the microscope. Leafhoppers in general are fast moving insects but they can be collected in an insect net or using a handheld vacuum (see EPP-25-3). You can submit samples to the OSU Plant Disease and Insect Diagnostic Lab.

Please feel free to reach out to OSU Cropping Systems Extension Entomologist Dr. Ashleigh Faris with any questions or concerns. @ ashleigh.faris@okstate.edu