Home » Posts tagged 'Double Crop'

Tag Archives: Double Crop

Toto, I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore. Double Cropping, Orange edition

It has been pointed out that the blog https://osunpk.com/2025/06/09/double-crop-options-after-wheat-ksu-edition/ had a significant Purple Haze. And I should have added the Oklahoma caveat. So Dr. Lofton has provided his take on DC corn in Oklahoma.

Double-crop Corn: An Oklahoma Perspective.

Dr. Josh Lofton, Cropping Systems Specialist.

Several weeks ago, a blog was published discussing double-crop options with a specific focus on Kansas. I wanted to address one part of that blog with a greater focus on Oklahoma, and that section would be the viability of double-crop corn as an option.

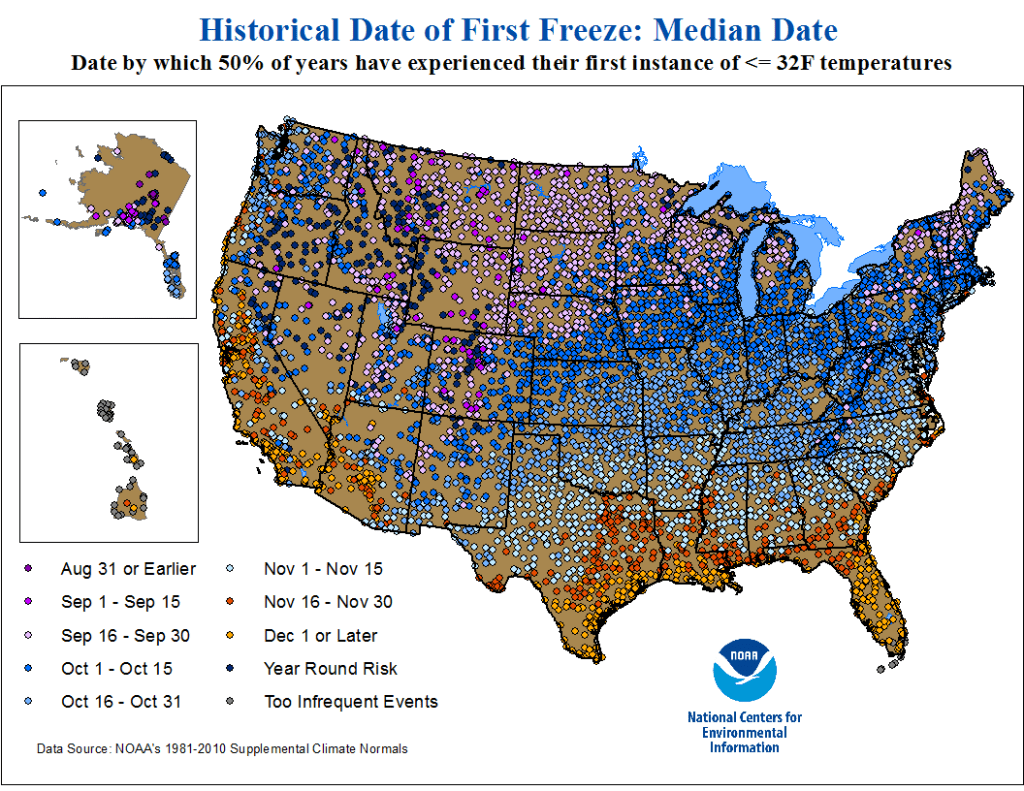

Double-crop farming is considered a high-risk, high-reward system to try. Establishing a crop during the hottest and often driest parts of summer can present challenges that need to be overcome. Double-crop corn faces these same challenges and, in some seasons, even more. However, it is definitely a system that can work in Oklahoma, especially farther south. If you look at that original blog post, one of the main challenges discussed is having enough heat units before the first frost. When examining historic data, like those below from NOAA, the first potential frost date for Northcentral and Northwest Oklahoma may be as early as the first 15 days of October but more often will be in the last 15 days of October. In Southwest and Central Oklahoma, this date shifts even later to the first 15 days of November. This is later than Kansas, especially northern Kansas, which has a much higher chance of experiencing an early October freeze. I do not want to downplay this risk; however, it is one of the biggest risks growers face with this system, and a later fall freeze would greatly benefit it. We have been conducting trials near Stillwater for the past five years on double-crop corn and have only failed the crop once due to an early freeze event. But in that year, both double-crop soybean and sorghum also did not perform well.

The main advantage of double-crop corn is that if you miss the early season window, it offers the best chance for the crop to reach pollination and early grain fill without the stress of the hottest and driest part of the year. Therefore, careful management is crucial to ensure this benefit isn’t lost. In Oklahoma, we have two systems that can support double-crop corn. In more central and southwest Oklahoma, especially under irrigation, farmers can plant corn soon after wheat harvest, similar to other double-crop systems. This planting window helps minimize the impact of Southern Rust, which can significantly reduce yields in some years, and may reduce the need for extensive management. This earlier planting window is often supported by irrigation, enabling the crop to endure the hotter, drier late July and early August periods. Conversely, in northern Oklahoma, planting often occurs in July to allow pollination and grain fill (usually 30-45 days after emergence) to happen in late August and early September. During this period, the chances of rainfall and cooler nighttime temperatures increase, both of which are critical for successful corn production.

Other management considerations include maturity. Based on initial testing in Oklahoma, particularly in the northern areas, we prefer to plant longer-maturity corn. Early corn varieties have a better chance of maturing before a potential early freeze but also carry a higher risk of undergoing critical reproduction stages (pollination and early grain fill) during hot, dry periods in late summer. Testing indicates that corn with a maturity of over 110 days often works well for this. However, this does not mean growers cannot plant shorter-season corn, especially if the season has generally been cooler, though the risk still exists depending on how quickly the crop can grow. Based on testing within the state, the dryland double-crop corn system typically does not require adjustments to other management practices, such as seeding rates or nitrogen application. Because of the need to coordinate leaf architecture and manage limited water resources, higher seeding rates are not recommended. Maintaining current nitrogen levels allows the crop to develop a full canopy.

The final question often comes as; how does it yield? This will depend greatly. Corn looks very good this year across that state, especially what was able to be planted earlier in the spring. However, in recent years, delaying even a couple of weeks beyond traditional planting windows has lowered yields enough that double-crop yields are often similar. We have often harvested between 50-120 bushels per acre in our plots around Stillwater with double-crop systems. So, the yield potential is still there.

In the end, Oklahoma growers know that double-crop is a risk regardless of the crop chosen. There are additional risks for double-crop corn, such as Southern Rust in the south and freeze dates in the north. This risk is increased by the presence of Corn Leaf Aphid and Corn Stunt last season, and it is not clear if these will be ongoing problems. Therefore, growers need to be careful not to expect too much or to invest too heavily in inputs that may not be recoverable if there is a loss. One silver lining is that if double-crop corn doesn’t succeed in any given year, growers can still use it as forage and recover at least some of their costs.

Any questions or concerns reach out to Dr. Lofton: josh.lofton@okstate.edu

Double Crop Response to Additional N, P, K and S.

Vaughn Reed, PhD. Student Precision Nutrient Management

Brain Arnall Precision Nutrient Management Extension Specialist.

Data presented below are the results of Mr. Reeds Masters research project.

On farm research trials are important, because they give us the ability to see responses over a larger geographic area, and even more importantly, evaluate our recommendations on fields that are managed by producers, not researchers. They also allow us to look at current production practices and see if there are any missed opportunities. Several years ago, we looked at whether producers were leaving yield on the table by not applying enough nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium(K), and sulfur (S) to winter wheat. We did this by applying strips of N, P, K, and S fertilizer on farmers’ fields with the instructions to not change their fertilizer management strategies. If one or more of the strips resulted in higher yields then it could be assumed that either the nutrient was under-applied by the producer, or in the case of N, lost. That study concluded that at 75% of the locations, yield was maximized by the producer with [their respective] NPKS management system, however the greatest responses came from the addition of P and that Oklahoma State University’s soil testing and analysis was adequate for nutrient recommendations. That studies results were published in 2017 and is open access, so available for anyone to read. https://dl.sciencesocieties.org/publications/cftm/abstracts/3/1/cftm2017.02.0014

There are many producers around the state that follow winter wheat with double crops (DC). Often, this practice is done with limited inputs to reduce economic risk. Oklahoma State does not make different recommendations for DC or full season crops, with the exception that yield potentials can differ. In 2016 and 2017 we duplicated the Wheat NPKS study across 3 double crops (soybean, grain sorghum, sunflower) following winter wheat and canola. With a recent climb in DC yields we wanted to investigate if producers were applying enough nutrients to maximize grain yield. Additionally it would allow us evaluate the accuracy of OSU’s soil test based fertilizer recommendations in a double crop. Over the two years, 61 on-farm sites ranging from central to NE Oklahoma had 200 lb/ac of product per nutrient applied in strips 6ft wide by 150 ft long. Urea (46-0-0), triple super phosphate (0-46-0), muriate of potash (0-0-60), and gypsum (0-0-0-19) were used for sources N, P, K, and S, respectively (92 lbs N, 92 lbs P, 120 lbs K, 38 lbs S). In most cases the fertilizer was applied post planting and post-emergence to ensure strips were applied an areas with good stand.

NPKS Strip Applicator. This ground driven 3pt rig uses Gandy boxes to deliver fertilizer into tubes which is then blown, by a PTO driven fan, out into strips 6 feet wide, per box. This applicator was putting out 200 lbs of Urea, 0-46-0, potash, and gypsum out per acre.

Much like with the wheat-NPKS study 75% of the locations did not respond to additional fertilizer. Twenty treatment comparisons of the 244 made across all 61 locations (50 soybean, 7 grain sorghum, 4 sunflower) yielded a statistically significant change in yield due to the addition of N-P-K-or S. For this report, a comparison was the yield of each nutrient versus the non-treated check, therefore there were four comparisons made per location. Seventeen of the twenty positive responses were found in soybean, three with grain sorghum, and no responses were found in sunflower plots. Lack of response from grain sorghum and sunflower locations is contributed to small amount of grain sorghum and sunflower fields in the study.

Double crop soybeans in Ottawa County with strips of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and sulfur applied post plant.

Nitrogen rates, for non-legumous crops, are yield driven, meaning the higher yielding a crop, the higher amount of N required. Both grain sorghum and sunflower crops, due to neither being legumes, were expected to see N response, especially to those locations that applied little to no N to begin with. A yield response from the addition of N was found in one grain sorghum location, where the producer application was not enough to maximize yield, and the additional N pushed the yields. As expected, there were no soybean locations that responded to the addition of N.

Phosphorus and potassium are both sufficiency based, not yield driven. This means that if the soil is at 100% sufficiency, the crop will produce at its highest rate achievable, based on that nutrient. 100% sufficiency for P and K are approximately 65 STP and 250 STK, respectively. Phosphorus and potassium strips yielded the most results, especially in soybean locations. Of 20 responses, five responses were due to P, ten due to K, and four due to S. Locations that responded to the addition to P were locations that either had low levels of STP (approx. 80% sufficiency or less), or had low pH, which leads to less availability of P (pH>5.0).

Potassium yielded the most positive results, with ten responsive locations, as well as the most interesting results, with only three sites falling below 100% sufficiency. The other responses were attributed to having low Cl levels (Cl, as in Chloride, which while responses are rare, is a necessary nutrient, and sometimes can lead to losses in yield, especially in sandy environments), as well as drought stress conditions. Potassium has been shown to have a vital role in nutrient uptake and water retention, as it is found to be critical for root growth, and these are displayed highest in crops found in drought like conditions. One hypothesis for the K response is related to root growth. The later planted DC will spend less resources in root development before going reproductive. Soybean is a heavy user of K, combine smaller roots, typically hot drier soils, and high K demand it is not surprising to find this occurrence.

Sulfur, while not wide-spread reported in Oklahoma, has recommendations by OSU built on a yield driven scale. There were four responsive locations found in this project. While one location had low soil test S values there were located areas that received high rainfall events during the growing season, and therefore the response was attributed to leaching of S.

So, after all that, what is the bottom line? Here is our observations:

- Producers maximized yield 75% of the time, with 25% of locations responding to any additional nutrient.

- The 20 responses to additional nutrients occurred across 15 locations, four locations had responses to more than one nutrient

- By nutrient: Note for P and K, due to site variability it was not expected to observe statistic yield increase due to P or K unless soil test was below 70% sufficiency, of which no location had soil test P or K below 70%.

- 38 locations were below 100% sufficiency of phosphorus, with five observed responses

- Seven locations were below 100% sufficiency of potassium, two observed responses. An additional eight locations responded that were not predicted by soil test

- Based on pre-plant soil test there were no sites expected to respond to the addition of Sulfur, 4 locations did respond.

- Soil test results were adequate in correctly identifying locations that would not respond to the addition of nutrients (93.5% accurate), while not as accurate at predicting sites that would respond.

- For K, soil testing was less accurate, as eight of the ten responsive locations had soil test values above 250 soil test K (125 ppm or 100% sufficiency). For this reason, we are currently doing work evaluating K recommendations for soybeans.

This work confirms that of the fields we evaluated, the majority was not yield limited by N, P, K or S. However, as with anything, we have more work to do in order to further refine our recommendations, and always looking to learn more about how to aid producers.