Home » sorghum

Category Archives: sorghum

Thoughts from an Agronomist- 1 Management of the Primordia

Josh Lofton, Cropping Systems Specialist

Many crop management recommendations emphasize actions that must be taken well before a crop reaches what we often call “critical growth stages.” Management this early can seem counterintuitive when the crop still looks small, healthy, or unchanged aboveground. However, much of a crop’s yield potential is determined early in the season at a level we cannot see in the field. Long before flowers, tassels, or heads (or any reproductive structure) appear, the plant is already making developmental decisions that shape its final yield potential. Understanding this “behind the scenes” process helps explain why timely, early-season management is often more effective than trying to correct problems later.

At the center of this process is the shoot apical meristem, commonly referred to as the growing point. This tissue produces leaf and reproductive primordia, which are the earliest developmental stages of future everything in the plant. These primordia form well before the corresponding plant parts are visible. Once these structures initiate—or if they fail to begin due to stress—the outcome is permanent. The plant cannot later in the season go back and recreate leaf number, leaf size, or reproductive capacity. As a result, early environmental conditions and management decisions play a disproportionate role in determining yield potential.

Corn is a good example of how early development influences final yield. By the time corn reaches the V4 growth stage, the plant only has four visible leaves with collars, yet internally it is far more advanced. Most of the total leaf primordia that will eventually form the full canopy have already begun, and the potential size of the ear is starting to be established. During this stage, the growing point is still below the soil surface and somewhat protected from some stressors but highly susceptible to others. Nitrogen deficiency, cold temperatures, moisture stress, compaction, or herbicide injury at or before V4 can reduce leaf number and limit leaf expansion. Even if growing conditions improve later, the plant cannot replace leaf primordia that were never formed, which reduces its ability to intercept sunlight and support high yields.

As corn approaches tasseling (VT), the crop enters a stage that is visually and physiologically important. Pollination, fertilization, and early kernel development occur at this time, and stress can have a critical impact on kernel set. However, by VT, the plant has already completed leaf formation, and much of the ear size potential has already been determined several growth stages earlier. Management at VT is therefore focused on protecting yield rather than creating it. Late-season nutrient applications may improve plant appearance or maintain green leaf area, but they cannot increase leaf number or rebuild ear potential lost due to early-season stress. This distinction helps explain why some late inputs show limited yield response even when the crop looks responsive.

Grain sorghum provides another clear example of why early management is emphasized. Although sorghum often grows slowly early in the season and may appear unimportant during the first few weeks after emergence, the first 30 days are among the most critical periods in its development. During this time, the growing point is actively producing leaf primordia and transitioning from vegetative growth toward reproductive development. Head size potential is primarily established during this early window, and the plant’s capacity to support tillers is influenced by early nutrient availability and moisture conditions. Stress from nitrogen deficiency, drought, weed competition, or restricted rooting during the first 30 days can reduce head size and kernel number long before visible symptoms appear.

Once sorghum reaches later vegetative and reproductive stages, much like corn at VT, management shifts from building yield potential to protecting what has already been determined. Improving conditions later in the season can help maintain plant health and grain fill, but it cannot fully compensate for early limitations imposed at the primordial level. This is why early fertility placement, timely weed control, and moisture conservation are consistently emphasized in sorghum production systems.

Across crops, a typical pattern emerges: the growth stages we observe in the field often reflect decisions the plant made weeks earlier. When agronomists stress early-season management, they are responding to plant biology rather than simply following tradition. By the time visible “critical stages” arrive, the plant has already established many of the components that define yield potential.

The key takeaway is that effective crop management must be proactive rather than reactive. Early-season decisions support the crop while it is still determining how many leaves it can produce, how large its reproductive structures can become, and how much yield it can ultimately support. Waiting until stress becomes visible often means responding after the plant has already adjusted its potential downward. Recognizing what is happening at the primordial level helps explain why management ahead of critical stages consistently delivers the greatest return, even when the crop appears small and unaffected aboveground.

For questions or comments reach out to Dr. Josh Lofton

josh.lofton@okstate.edu

Double Crop Options After Wheat (KSU Edition)

Stolen from the KSU e-Update June 5th 2025.

Double cropping after wheat harvest can be a high-risk venture for grain crops. The remaining growing season is relatively short. Hot and/or dry conditions in July and August may cause problems with germination, emergence, seed set, or grain fill. Ample soil moisture this year can aid in establishing a successful crop after wheat harvest. Double-cropping forages after wheat works well even in drier regions of the state.

The most common double crop grain options are soybean, sorghum, and sunflower. Other possibilities include summer annual forages and specialized crops such as proso millet or other short-season summer crops, even corn. Cover crops are also an option for planting after wheat (see the companion eUpdate article “Cover crops grown post-wheat for forage”).

Be aware of herbicide carryover potential

One major planting consideration after wheat is the potential for herbicide carryover. Many herbicides applied to wheat are Group 2 herbicides in the sulfonylurea family with the potential to remain in the soil after harvest. If a herbicide such as chlorsulfuron (Glean, Finesse, others) or metsulfuron (Ally) has been used, then the most tolerant double crop will be sulfonylurea-resistant varieties of soybean (STS, SR, Bolt) or other crops. When choosing to use herbicide-resistant varieties, be sure to match the resistance trait with the specific herbicide (not only the herbicide group) that you used. This is especially true when looking at sunflowers as a double crop. There are sunflowers with the Clearfield trait, which allows Beyond herbicide applications, and ExpressSun sunflowers, which allow an application of Express herbicide. While both of these herbicides are Group 2 (ALS-inhibiting herbicides), the Clearfield trait and ExpressSun are not interchangeable, and plant damage can result from other Group 2 herbicides.

Less information is available regarding the herbicide carryover potential of wheat herbicides to cover crops. There is little or no mention of rotational restrictions for specific cover crops on the labels of most herbicides. However, this does not mean there are no restrictions. Generally, there will be a statement that indicates “no other crops” should be planted for a specified amount of time, or that a bioassay must be conducted prior to planting the crop.

Burndown of summer annual weeds present at planting is essential for successful double-cropping. Assuming glyphosate-resistant kochia and pigweeds are present, combinations of glyphosate with products such as saflufenacil (Sharpen) or tiafenacil (Reviton), or alternative treatments such as paraquat may be required. Dicamba or 2,4-D may also be considered if the soybean varieties with appropriate herbicide resistance traits are planted. In addition, residual herbicides for the double crop should be applied at this time.

Management, production costs, and yield outlooks for double crop options are discussed below.

Soybeans

Soybeans are likely the most commonly used crop for double cropping, especially in central and eastern Kansas (Figure 1). With glyphosate-resistant varieties, often the only production cost for planting double crop soybeans was the seed, an application of glyphosate, and the fuel and equipment costs associated with planting, spraying, and harvesting. However, the spread of herbicide-resistant weeds means additional herbicides will be required to achieve acceptable control and minimize the risk of further development of resistant weeds.

Weed control. The weed control cost cannot really be counted against the soybeans, since that cost should occur whether or not a soybean crop is present. In fact, having soybeans on the field may reduce herbicide costs compared to leaving the field fallow. Still, it is recommended to apply a pre-emergence residual herbicide before or at planting time. Later in the summer, a healthy soybean canopy may suppress weeds enough that a late-summer post-emergence application may not be needed.

Variety selection for double cropping is important. Soybeans flower in response to a combination of temperature and day length, so shifting to an earlier-maturing variety when planting late in a double crop situation will result in very short plants with pods that are close to the ground. Planting a variety with the same or perhaps even slightly later maturity rating (compared to soybeans planted at a typical planting date) will allow the plant to develop a larger canopy before flowering. Planting a variety that is too much later in maturity, however, increases the risk that the beans may not mature before frost, especially if long periods of drought slow growth. The goal is to maximize the length of the growing season of the crop, so prompt planting after wheat harvest time is critical. The earlier you can plant, the higher the yield potential of the crop if moisture is not a limiting factor.

Fertilizer considerations. Adding some nitrogen (N) to double-crop soybeans may be beneficial if the previous wheat yield was high and the soil N was depleted. A soil test before wheat harvest for N levels is recommended. Use no more than 30 lbs/acre of N. It would be ideal to knife-in the fertilizer. If that is not possible, banding it on the soil surface would be acceptable. Do not apply N in the furrow with soybean seed as severe stand loss can occur.

Seeding rates and row spacing. Seeding rate can be slightly increased if soybeans are planted too late in order to increase canopy development. Narrow row spacing (15-inch or less) has often resulted in a yield advantage compared to 30-inch rows in late plantings. Soybeans planted in narrow rows will canopy over more quickly than in wide rows, which is important when the length of the growing season is shortened. Narrow rows also offer the benefits of increasing early-season light capture, suppressing weeds, and reducing erosion. On the other hand, the advantage of planting in wide rows is that the bottom pods will usually be slightly higher off the soil surface to aid harvest. The other consideration is planting equipment. Often, no-till planters will handle wheat residue better and place seeds more precisely than drills, although the difference has narrowed in recent years.

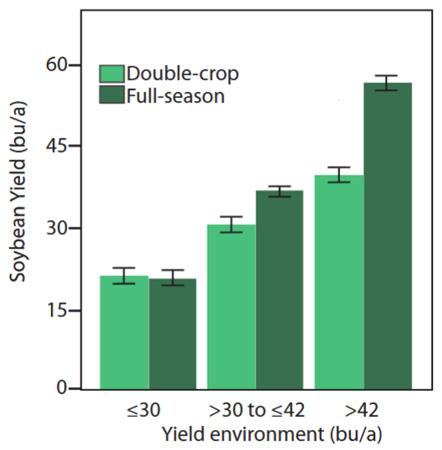

What are typical yield expectations for double-crop soybeans? It varies considerably depending on moisture and temperature, but yields are usually several bushels less than full-season soybeans. A long-term average of 20 bushels per acre is often mentioned when discussing double-crop soybeans in central and northeast Kansas. Rainfall amount and distribution can cause a wide variation in yields from year to year. Double-crop soybean yields typically are much better as you move farther southeast in Kansas, often ranging from 20 to 40 bushels per acre.

A recent publication explores the potential yield of double-crop soybeans relative to full-season yield (Figure 2) and the most limiting factors affecting the yields for double-crop soybeans. The link to this article is: https://bookstore.ksre.ksu.edu/pubs/MF3461.pdf.

Grain Sorghum

Grain sorghum is another double crop option. Unlike soybeans, sorghum hybrids for double cropping should be earlier maturing hybrids. Sorghum development is primarily driven by the accumulation of heat units, and the double crop growing season is too short to allow medium-late or late hybrids to mature before the first frost in most of Kansas.

Seeding rates and row spacing. Late-planted sorghum likely will not tiller as much as early plantings and can benefit from slightly higher seeding rates than would be used for sorghum planted at an earlier date. Narrow row spacing is advised, especially if the outlook for rainfall is good.

Fertilizer considerations. A key component for the estimation of N application rates is the yield potential. This will largely determine the N needs. It is also important to consider potential residual N from the wheat crop. This can be particularly important when wheat yields are lower than expected. In that situation, additional available N may be present in the soil. Assess the amount of profile N by taking soil samples at a depth of 24 inches and submitting them for analysis at a soil testing laboratory.

Double crop sorghum planted into average or greater-than-average amounts of wheat residue can result in a challenging amount of residue to deal with when planting next year’s crop. Nitrogen fertilizer can be tied up by wheat residue, so use application methods to minimize tie-up, such as knifing into the soil below the residue.

Weed control. Weed control can be important in double-crop sorghum. Warm-season annual grasses, such as crabgrass, can reduce double-crop sorghum yields. Using a chloroacetamide-and-atrazine pre-emergence product may be key to successful double-crop sorghum production. Herbicide-resistant grain sorghum varieties will allow the use of imazamox (Imiflex in igrowth sorghums) or quizalofop (FirstAct in DoubleTeam grain sorghum) that can control summer annual grasses.

No-till studies at Hesston documented 4-year average double crop sorghum yields of 75 bushels per acre compared to about 90 bushels per acre for full-season sorghum. A different 10-year study that did not have double crop planting but did compare early- and late-planting dates averaged 73 bushels per acre for May planting vs. 68 bushels per acre for June planting.

Sunflowers

Sunflowers can be a successful double crop option anywhere in the state, provided there is enough moisture at planting time to get a stand. Sunflowers need more moisture than any other crop to germinate and emerge because of the large seed. Therefore, stand establishment is important. Planting immediately after wheat harvest on a limited irrigation field can be a good fit to help with stand establishment.

Seeding rates and hybrid selection. When double-cropping sunflowers, producers should use similar seeding rates to what is typical for the area for full-season sunflowers. While full-season sunflowers can be successful in double-crop production, utilizing shorter-season hybrids can increase the likelihood of the sunflowers blooming and maturing before a killing frost.

Weed control. First, it is important to check the herbicide applications on the wheat. The rotation restriction to sunflowers after several commonly used wheat herbicides is 22-24 months.

Weed control can be an issue with double-crop sunflowers since herbicide options are limited, especially post-emergence. Thus, controlling weeds prior to sunflower planting is critical and may be complicated pre-plant restrictions for some herbicides. Planting Clearfield or ExpressSun sunflowers will provide additional post-emergence herbicide options, but ALS-resistant kochia and pigweeds still won’t be controlled. Imazamox (Beyond in Clearfield sunflower) has activity on small annual grasses as well as many broadleaf weeds, if they are not ALS-resistant.

Summer annual forages

With mid-July plantings, and where herbicide carryover issues are not a concern, summer annual sorghum-type forages are also a good double crop option. A study planted July 21, 2008 near Holton, when summer rainfall was very favorable, provided yields of 2.5 to 3 tons dry matter/acre for hybrid pearl millet and sudangrass at the low end to 4 to 5 tons dry matter/acre for forage sorghum, BMR forage sorghum, photoperiod sensitive forage sorghum, and sorghum x sudangrass hybrids. Earlier plantings may produce even more tonnage, as long as there is adequate August rainfall.

One challenge with late-planted summer annual forages is getting them to dry down when harvest is delayed until mid- to late-September. Wrapping bales or bagging to make silage are good ways to deal with the higher moisture forage this late in the year.

Corn

Is double-crop corn a viable option? Corn is typically not recommended for late June or July plantings because yield is usually substantially less than when planted earlier.

Typically, mid-July planted corn struggles during pollination and seldom receives sufficient heat units to fill grain before frost. Very short-season corn hybrids (80 to 95 RM) have the greatest chance of maturing before frost in double crop plantings, but generally have less yield potential when compared to hybrids of 100 RM or more used for full-season plantings. Short-season hybrids often set the ear fairly close to the ground, increasing the harvest difficulty. Glyphosate-resistant hybrids will make weed control easier with double crop corn, but problems remain present with late-emerging summer weeds such as pigweeds, velvetleaf, and large crabgrass. Keep in mind, corn is very susceptible to carryover of most residual ALS herbicides used in wheat.

Considerations for altering seeding rates and variety/hybrid maturity for the crops discussed above are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Seeding rate and variety/hybrid relative maturity considerations for double crops compared to full-season.

| Crop | Seeding rate | Relative maturity |

| ???????? Difference between double crop and full-season ???????? | ||

| Soybean | Increase | No change or longer |

| Sorghum | Increase | Shorter |

| Sunflower | No change | Shorter |

| Corn | No change | Shorter |

Volunteer wheat control

One of the issues with double cropping that is often overlooked by producers is the potential for volunteer wheat in the crop following wheat. If volunteer wheat emerges and goes uncontrolled, it can cause serious problems for nearby wheat fields in the fall as a host for the wheat streak mosaic complex of viruses [wheat streak mosaic (WSMV), High Plains disease (HPD), and triticum mosaic (TriMV)] that are transmitted by the wheat curl mite (WCM).

Volunteer wheat can generally be controlled fairly well with glyphosate or Group 1 herbicides such as quizalofop (Assure II, others), clethodim (Select Max, others), or sethodydim (Poast Plus, others), but control is reduced during times of drought stress. Atrazine can provide control of volunteer wheat in double-crop corn or sorghum, but control can be erratic depending on rainfall patterns.

For more detailed information about herbicides, see the “2025 Chemical Weed Control for Field Crops, Pastures, and Noncropland” guide available online at https://www.bookstore.ksre.ksu.edu/pubs/CHEMWEEDGUIDE.pdf or check with your local K-State Research and Extension office for a paper copy. The use of trade names is for clarity to readers and does not imply endorsement of a particular product, nor does exclusion imply non-approval. Always consult the herbicide label for the most current use requirements.

To Subscribe to the KSU Agronomy E-Updates follow this link

https://eupdate.agronomy.ksu.edu/index_new_prep.php

Authors contributing to the post

Sarah Lancaster, Weed Management Specialist

slancaster@ksu.edu

John Holman, Cropping Systems Agronomist

jholman@ksu.edu

Logan Simon, Southwest Area Agronomist

lsimon@ksu.edu

Tina Sullivan, Northeast Area Agronomist

tsullivan@ksu.edu

Jeanne Falk Jones, Multi-County Agronomist

jfalkjones@ksu.edu

Sorghum Nitrogen Timing

Contributors:

Josh Lofton, Cropping Systems Specialist

Brian Arnall, Precision Nutrient Specialist

This blog will bring in a three recent sorghum projects which will tie directly into past work highlighted the blogs https://osunpk.com/2022/04/07/can-grain-sorghum-wait-on-nitrogen-one-more-year-of-data/ and https://osunpk.com/2022/04/08/in-season-n-application-methods-for-sorghum/

Sorghum N management can be challenging. This is especially true as growers evaluate the input cost and associated return on investment expected for every input. Recent work at Oklahoma State University has highlighted that N applications in grain sorghum can be delayed by up to 30 days following emergence without significant yield declines. While this information is highly valuable, trials can only be run on certain environmental conditions. Changes in these conditions could alter the results enough to impact the effect delay N could have on the crop. Therefore, evaluating the physiological and phenotypic response of these delayed applications, especially with varied other agronomic management would be warranted.

One of the biggest agronomic management sorghum growers face yearly is planting rate. Growers typically increase the seeding rate in systems where specific resources, especially water, will not limit yield. At the same time, dryland growers across Oklahoma often decrease seeding rates by a large margin if adverse conditions are expected. If seeding rates are lowered in these conditions and resources are plentiful, sorghum often will develop tillers to overcome lower populations. However, if N is delayed, there is a potential that not enough resources will be available to develop these tillers, which could decrease yields.

A recent set of trials, summarized below, shows that as N is delayed, the number of tillers significantly decreases over time. Furthermore, the plant cannot overcompensate for the lower number of productive heads with significantly greater head size or grain weight.

This information shows that delaying sorghum N applications can still be a viable strategy as growers evaluate their crop’s potential and possible returns. However, delayed N applications will often result in a lower number of tillers without compensating with increased primary head size or grain weight.

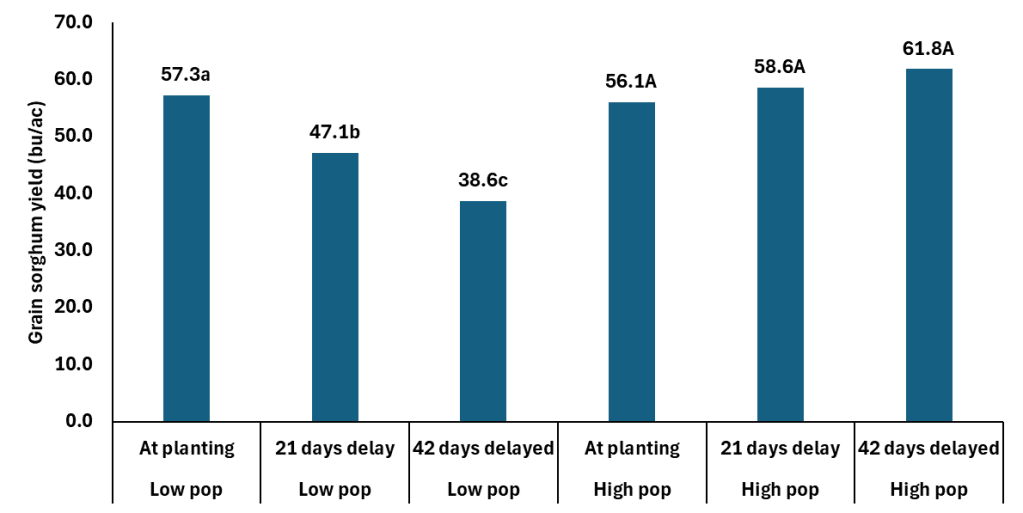

This date on yield components is really interesting when you then consider the grain yield data. The study, which is where the above yield component data came from, was looking at population by N timing. The Cropping Systems team planted 60K seeds per acre and hand thinned the stands down to 28 K (low) and 36K (high). The N was applied at planting, 21 days after emergence, and 42 days after emergence. The rate of N applied was 75 lbs N ac. It should be noted both locations were responsive to N fertilizer.

In the data you can without question see how the delayed N management is not a tool for any of members of the Low Pop Mafia. However those at what is closer to mid 30K+ there is no yield penalty and maybe a yield boost with delayed N. The extra yield is coming from the slightly heavier berries and getting more berries per head. Which is similar to what we are seeing in winter wheat. Delaying N in wheat is resulting in fewer tillers at harvest, but more berries per head with slightly heavier berries.

Now we can throw even more data into the pot from the Precision Nutrient Management Teams 2024 trials. The first trial below is a rate, time and source project where the primary source was urea applied in front of the planter for pre in range of rates from 0-180 in 30 lbs increments. Also applied pre was 90 lbs N as Super U. Then at 30 days after planted we applied 90 lbs N as urea, SuperU, UAN, and UAN + Anvol.

Pre-plant urea topped out at 150 lbs of Pre-plant (57 bushel), but it was statistically equal to 90 lbs N 51 bushel. The use of SuperU pre did not statistically increase yield but hit 56 bushel. The in-season shots of 90 lbs of UAN, statistically outperformed 90 pre and hit our highest yeilds of 63 and 62 bushel per acre. The dry sources in-season either equaled their in preplant counter parts.

The Burn Study at Perkins, showed that the N could be applied in-season through a range of methods, and still result good yields. In this study 90 lbs of N was used and applied in a range of methods. The treatments for this study was applied on a different day than the N source. Which you can see in this case the dry untreated urea did quite well when when applied over the top of sorghum. In this case we are able to get a rain in just two days. So we did get good tissue burn but quick incorporation with limited volatilization.

Take Home:

Unless working in low population scenarios. The data show that we should not be getting into any rush with sorghum and can wait until we know we have a good stand. We also have several options in terms of nitrogen sources and method of application.

Any questions or comments feel free to contact Dr. Lofton or myself

josh.lofton@okstate.edu

b.arnall@okstate.edu

Funding Provided by The Oklahoma Fertilizer Checkoff, The Oklahoma Sorghum Commission, and the National Sorghum Growers.